Insular Celtic languages

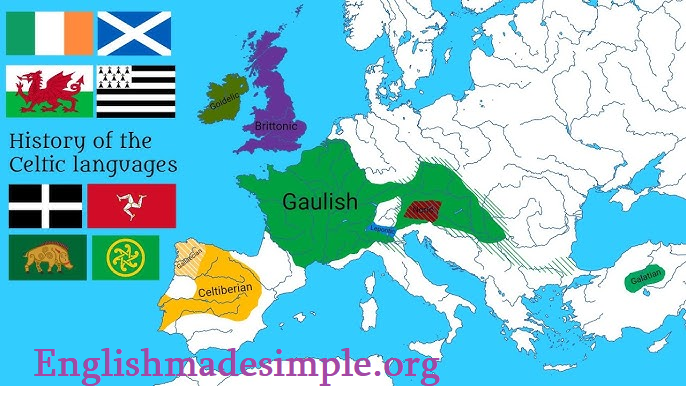

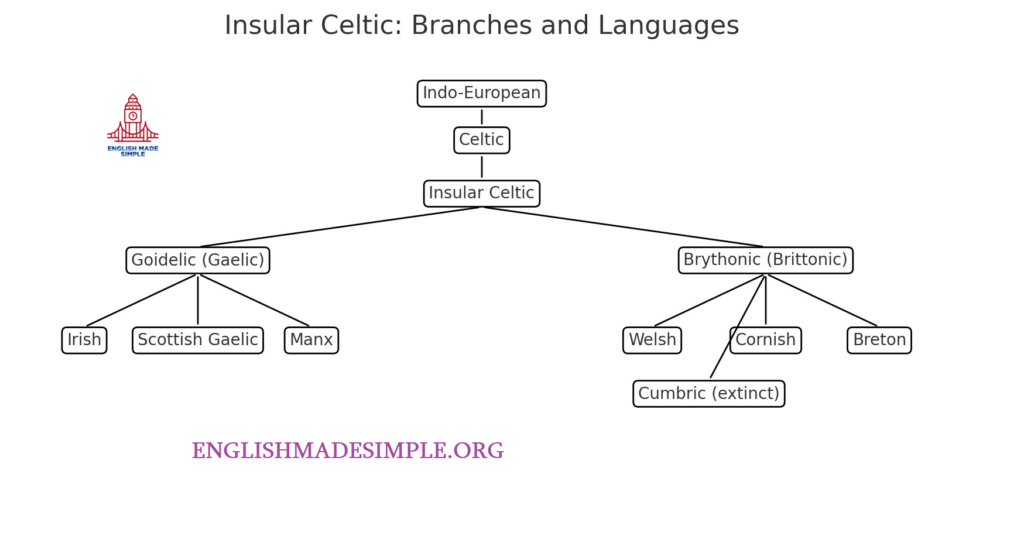

The Insular Celtic languages form one of the two principal divisions of the Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family. They are the Celtic languages that developed in and around the islands of Britain and Ireland, in contrast to Continental Celtic languages once spoken on the European mainland (e.g., Gaulish, Celtiberian, Lepontic, Noric), now extinct. Within Insular Celtic, scholars conventionally recognise two sub-branches:

-

Goidelic (Gaelic): Irish (Gaeilge), Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), and Manx (Gaelg).

-

Brythonic (Brittonic): Welsh (Cymraeg), Cornish (Kernowek), Breton (Brezhoneg), and the extinct Cumbric.

Insular Celtic thus sits alongside other Indo-European branches such as Italic (including Latin and the Romance languages), Germanic, Balto-Slavic, Hellenic (Greek), and Indo-Iranian, among others. Some comparative work has argued for an ancient “Italo-Celtic” layer (shared early innovations between Italic and Celtic), but this remains a debated hypothesis rather than a settled subgrouping.

You can use these simple diagrams for orientation:

-

Branches: Download diagram

-

Timeline: Download diagram

Origins and early development

The Proto-Celtic language, the reconstructed ancestor of all Celtic languages, emerged from the wider Proto-Indo-European continuum in late Bronze Age to early Iron Age Europe. By the first millennium BCE, Celtic languages were spoken across a broad swathe of Europe. The branch that ultimately became Insular Celtic crystallised in the British Isles, where it diverged from Continental varieties both through geographical separation and through a suite of sound and grammatical innovations that would come to characterise the island languages.

A hallmark of Celtic prehistory is the scarcity of early continuous texts. On the mainland the epigraphic record is fragmentary. In the islands, the first clear linguistic traces appear in Primitive Irish, preserved primarily in Ogham inscriptions (roughly 4th–6th centuries CE). Meanwhile, the speech of Roman-era Britain is generally referred to as Common Brittonic, the ancestor of Welsh, Cornish and Breton (the last arising in Armorica from migration from Britain in the early medieval centuries).

Two high-level tendencies are often noted in the emergence of Insular Celtic:

-

Phonological and morphosyntactic innovation: Insular Celtic languages (especially Brythonic) developed initial consonant mutations, and the family exhibits verb-initial (VSO) basic word order in many contexts. The group also shows inflected prepositions (prepositions fused with pronominal endings).

-

Divergence under geographic and political pressures: Separate polities, monastic centres, and patterns of literacy encouraged divergence—particularly between Ireland (and later Gaelic Scotland and Man) and the Brittonic-speaking regions of Wales, Cornwall and Brittany.

Sub-branches

Goidelic (Gaelic)

The Goidelic languages descend from Primitive Irish → Old Irish → Middle Irish, from which later diverge Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx.

-

Primitive Irish (Ogham) (c. 4th–6th centuries). These short inscriptions, usually personal names, show an early Celtic language on Irish soil, written in a distinctive alphabet of strokes and notches. They bridge the gap between Continental epigraphy and the rich medieval Irish manuscript tradition.

-

Old Irish (c. 6th/7th–9th centuries). With the spread of Christianity, Latin script literacy arrived. Old Irish appears in glosses, law tracts, poetry and prose. The language shows complex inflectional morphology, verb-initial syntax, and a rich consonantal system.

-

Middle Irish (c. 10th–12th centuries). A period of levelling and change, Middle Irish is the common ancestor of later Irish and Scottish Gaelic. It is the lingua franca of a major literary culture, including sagas and ecclesiastical literature.

-

Early Modern Irish and diversification (c. 13th–17th centuries). Regional varieties sharpen. Scottish Gaelic emerges as a distinct literary and spoken norm in the Highlands and Islands. Manx, brought to the Isle of Man by Gaelic settlers and shaped by insular contact, develops its own orthographic and phonological profile.

-

Modern Irish (post-17th century), Scottish Gaelic, and Manx. In the modern period, each language faces social and political pressures from English and Scots. Irish retains official status in Ireland with robust revival efforts; Scottish Gaelic sustains education and media presence in Scotland; Manx underwent severe decline in the 19th–20th centuries but has seen a notable 20th–21st-century revival, culminating in new generations of native-style speakers.

Shared features within Goidelic include a reflex of Proto-Celtic *kʷ as c/k (hence “Q-Celtic”), verb-initial syntax, and comparable verbal systems—though the three languages today are not mutually intelligible without study.

Brythonic (Brittonic)

The Brythonic languages descend from Common Brittonic (Iron Age and Roman Britain) and branch into Welsh, Cornish, Breton, plus the now-extinct Cumbric of northern Britain.

-

Common Brittonic (to c. 6th century). The vernacular Celtic speech of most of Britain before and during Roman rule. Post-Roman migrations carried a Brittonic variety to Armorica (Brittany), seeding Breton.

-

Welsh. Conventionally divided into Old Welsh (c. 8th–11th centuries), Middle Welsh (c. 12th–14th), and Modern Welsh (from c. 16th). It boasts one of Europe’s oldest continuous vernacular literatures, including the Mabinogion material (transmitted in later manuscripts) and a strong bardic tradition. Welsh underwent sound changes that yielded its characteristic system of initial mutations, rich consonant inventory, and distinctive orthography.

-

Cornish. Flourished in medieval Cornwall; underwent attrition from the 16th century amid sociolinguistic change and anglicisation. Late Cornish persisted into the 18th century. The 20th century saw a revival and standardisation efforts, with contemporary Cornish now taught and used ceremonially and culturally.

-

Breton. Transplanted from Britain to Brittany in late antiquity/early medieval times, Breton developed on the European mainland yet is structurally Brythonic. It shows Old, Middle and Modern stages paralleling Welsh, and exists today with multiple dialects and a significant cultural presence despite language-shift pressures from French.

-

Cumbric (extinct). A Brythonic variety once spoken in the “Old North” (Cumbria/Strathclyde). It likely died out by the high medieval period, leaving onomastic traces.

Common Brythonic features include P-Celtic reflexes (Proto-Celtic *kʷ > p), a well-developed mutation system, and shared lexicon and morphology across the three living daughters (Welsh, Cornish, Breton).

Structural profile of Insular Celtic

Although the Goidelic and Brythonic branches differ in their sound correspondences and much vocabulary, they share a suite of typological features unusual within Europe:

-

Word order: Frequently VSO (verb–subject–object) in main clauses, especially in older stages and in formal registers; modern usage can be more flexible, but verb-initial structure remains core to clause syntax.

-

Initial consonant mutations: Grammatically conditioned alternation of a word’s initial consonant (e.g., Welsh pen “head” → ben after certain triggers). Mutations mark syntactic relationships (following prepositions, possessors, numerals, etc.).

-

Inflected (conjugated) prepositions: Prepositions inflect for person/number of their pronominal complements (e.g., Irish agam “at me” from ag “at” + first-person ending).

-

Prepositional periphrasis: Many argument structures and adverbials are prepositional; possession, existence, and experience are often expressed with prepositional constructions rather than a plain “have” verb.

-

Verbal systems: Rich sets of preverbal particles (for tense, aspect, mood, polarity), along with synthetic/analytic alternations. Older stages show broad initial mutation triggered by these particles.

-

Nouns and cases: Old Irish maintained a multi-case system that simplified over time; modern Insular Celtic tends towards prepositional marking rather than robust case morphology.

-

Lenition and palatalisation: Systematic consonant weakening and contrastive palatalisation in Goidelic; Brythonic develops its own conditioned alternations.

These shared traits are part inheritance, part convergent development in the insular context. They set Insular Celtic apart from much of continental Europe’s languages.

Contact, borrowing, and writing

Contact has been pervasive:

-

Latin influenced both sub-branches, especially in ecclesiastical vocabulary and learned registers. Brittonic in Roman Britain absorbed Latin loanwords; Irish borrowed heavily with Christianisation.

-

Norse and English/Scots impacted Goidelic and Brythonic in different periods (loanwords, place-names, and in some areas grammatical calques).

-

French has affected Breton lexicon and usage due to prolonged bilingualism.

Scripts and orthographies evolved from Ogham (Primitive Irish) to Latin script for all later stages. Orthographic reforms in modern times (e.g., the Irish post-1940s spelling standard; Welsh standardisation; Cornish revival standards; Manx based on English-style values) reflect both historical continuity and modern pedagogy.

Sociolinguistic status and revitalisation

All living Insular Celtic languages are minority languages within their states or regions, with varying degrees of institutional support:

-

Irish is an official and national language of Ireland, used in education, media, and public life, with Gaeltacht regions retaining community transmission.

-

Scottish Gaelic enjoys recognition in Scotland, with schooling, broadcasting, and cultural initiatives underpinning maintenance.

-

Manx, once declared moribund after the death of the last traditional native speaker in the 20th century, now has a small but growing cohort of new speakers, including children educated through Manx.

-

Welsh has a strong institutional framework in Wales, with significant daily usage, bilingual education, and ambitious policy targets for future speaker numbers.

-

Cornish and Breton sustain vibrant cultural movements and educational programmes; Cornish is a revival language with increasing visibility, while Breton faces ongoing shift pressures but maintains active immersion schooling (Diwan) and cultural production.

Comparison with the continental Latin (Romance) languages

Although Insular Celtic and the Latin/Romance languages are both Indo-European, they occupy different branches—Celtic vs Italic—and diverged very early. Their histories have nevertheless been intertwined through contact (Roman Britain; medieval church Latin; later state languages). The following table summarises broad lexical and grammatical similarities and differences. “Insular Celtic” here refers to shared or typical traits of the Goidelic and Brythonic branches; “Romance” refers to continental daughters of Latin (e.g., French, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Romanian), noting that individual Romance languages vary.

| Category | Insular Celtic (Goidelic & Brythonic) | Continental Latin/Romance |

|---|---|---|

| Family | Celtic branch of Indo-European | Italic branch of Indo-European (Latin → Romance) |

| Shared ancestry | Distant: common Proto-Indo-European heritage; possible Italo-Celtic layer debated | Same distant ancestry; Romance directly descends from Latin |

| Basic word order | Often VSO in canonical clauses; verb-initial tendencies | Latin variable (often SOV/SVO); modern Romance largely SVO |

| Initial consonant mutations | Central to grammar (esp. Brythonic; also Goidelic lenition/eclipsis) | Absent as a grammatical system |

| Prepositions | Inflected (conjugated) prepositions (e.g., Irish agam “at me”) | Prepositions remain independent; clitics exist but not full paradigms |

| Case morphology (nouns) | Robust in Old Irish; greatly reduced in modern languages; heavy use of prepositions | Latin had rich case system; Romance languages largely lost cases (except pronouns; Romanian retains some) |

| Verbal morphology | Preverbal particles, analytic/synthetic alternations; periphrastic aspect common | Latin synthetic verb system → Romance synthetic + periphrastic forms (perfect, progressive, etc.) |

| Gender | Typically two genders (masc./fem.) in modern languages | Typically two (masc./fem.); Latin had three; Romanian preserves neuter-like behaviour |

| Plural formation | Mix of suffixal morphology and mutation triggers; some irregulars | Romance mostly suffixal (-s/-i/-e), with regular patterns across lexemes |

| Lexicon: inheritances | Shared PIE roots yield cognates (e.g., numerals; kinship terms) | Same; cognates visible across Romance and to Celtic via PIE |

| Lexicon: loans | Extensive Latin loans (church, administration, learning); English/French/Norse loans regionally | Celtic substrate in Gaul influenced French to a degree; many later loans between neighbouring languages |

| Phonology | Systematic lenition, palatalisation contrasts (Goidelic); complex mutation patterns (Brythonic) | Romance lenition mainly intervocalic and historical; no morphosyntactic mutation |

| Orthography | Historical spellings reflect mutations and palatalisation (Irish; Welsh digraphs); Manx uses English-style conventions | Latin alphabet with language-specific conventions; diacritics vary by language |

| Periphrastic possession | Possession often via prepositional constructions (e.g., “is at me”) | Romance uses “have” verbs (e.g., haber/avere/avoir) |

| Relative clauses | Frequently employ specialised particles and mutations | Latin had relative pronouns; Romance uses pronouns/particles without mutation effects |

| Mutual intelligibility | None with Romance; limited within Celtic across sub-branches without study | High mutual intelligibility among closely related Romance languages |

Similarities are primarily those expected of distant Indo-European relatives (cognates in basic vocabulary, some inherited grammatical categories such as gender and verbal inflection, and a general drift from synthetic to more analytic expression over time). Differences that stand out typologically are the Insular Celtic mutation systems, verb-initial syntax, and inflected prepositions—structures not replicated in Romance.

Historical timelines at a glance

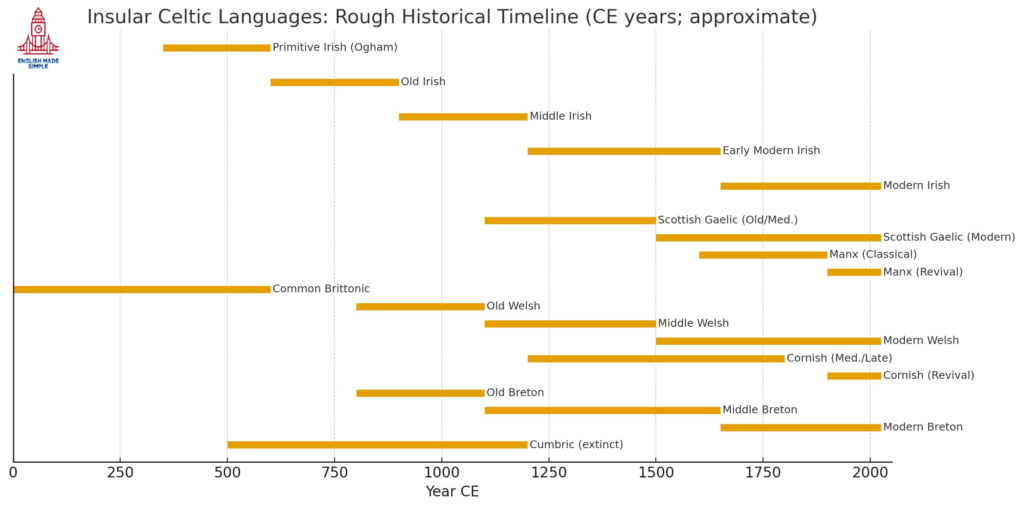

For a compact visual overview of periodisation and divergence, see:

-

Branches schematic (Insular Celtic within Indo-European, and its two sub-branches):

Branches diagram -

Rough historical timeline (major stages/languages from late antiquity to the present):

Timeline diagram

These are high-level guides rather than exhaustive chronologies; dates for linguistic stages are approximate and overlap.

Scholarship and debates

Two enduring topics frame Insular Celtic studies:

-

The Insular vs Continental division: While obvious geographically, the linguistic distinctiveness of Insular Celtic (mutations, VSO, inflected prepositions) suggests deep structural innovation after separation from the continental varieties. The extent to which these traits derive from internal drift versus areal contact within the British-Irish archipelago is debated.

-

Italo-Celtic hypothesis: Celtic and Italic share certain ancient innovations (e.g., particular morphological endings). Whether these reflect a genetic subgroup (an Italo-Celtic node) or early areal convergence among neighbouring dialects of Proto-Indo-European is unresolved. Regardless, by historical times the branches show clear separate trajectories.

Legacy and present outlook

Despite dramatic contraction from their early medieval footprints, Insular Celtic languages have proved resilient. They embody some of Europe’s longest continuous vernacular literatures (Welsh and Irish), have produced major medieval and modern corpora, and today animate cultural life, education, and media in their regions. State policies, immersion schooling, and community activism are shaping new domains of use and, in some cases, new generations of speakers.

As research subjects, Insular Celtic languages offer:

-

Comparative laboratories for syntax (verb-initial structures), morphology (mutation systems), and historical phonology (systematic lenition and palatalisation).

-

Case studies in language contact and shift (Latin, Norse, English/Scots, French).

-

Models for revival and maintenance, from Cornish and Manx standardisation to Welsh large-scale bilingualism and Irish Gaeltacht planning.

-

The timeline compresses many local developments into broad bands to illustrate relative chronology—e.g., Primitive Irish (Ogham), Old/Middle/Modern Welsh, emergence and revival phases for Cornish and Manx, and the approximate extinction window for Cumbric.

Download the timeline diagram

Conclusion

The Insular Celtic languages—Goidelic and Brythonic—are a distinctive cluster within the Indo-European family. They share a deep history on the Atlantic fringe of Europe, marked by striking structural features (VSO syntax, initial mutations, and inflected prepositions) and by intertwined literary traditions stretching back to the early medieval period. Their divergence from Continental Latin/Romance languages is both genealogical and typological, yet their long contact history has left clear lexical footprints on both sides.

Today, the Insular Celtic languages remain emblematic of cultural identity and linguistic diversity in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man, Wales, Cornwall and Brittany. Their study enriches our understanding of how languages evolve in relative isolation, how they adapt under intense contact, and how communities can sustain and rekindle linguistic heritage in the modern world.