Fula (Fulani, Fulfulde, Pulaar, Pular)

Overview.

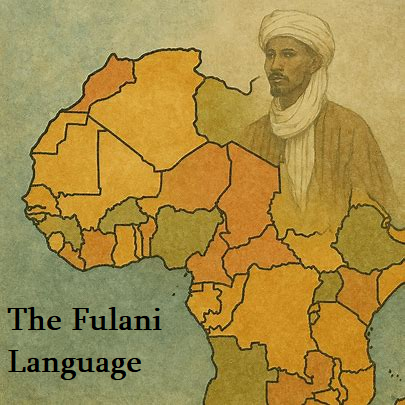

Fula — also called Fula, Fulani, Fulah, or in the language’s own names Fulfulde, Pulaar or Pular — is a broad dialect-continuum of closely related varieties spoken by the Fula (Fulbe) peoples across much of the West and Central African Sahel and savannah belt. It functions both as a first language for many Fulbe communities and as a regional lingua franca in large parts of West Africa. Estimates place total speakers in the tens of millions (commonly cited figures range from about 30–37 million first-language speakers, with many more second-language users).

Classification and related languages

Fula is classified within the Niger–Congo phylum. More precisely it is usually placed in the Atlantic (West Atlantic / Senegambian) group and the Senegambian branch (a subgroup often listed with Wolof and Serer). Within that branch Fula is sometimes treated as forming a Fula–Wolof grouping or as the type language of the Senegambian cluster. Although genealogically related to Wolof and Serer, Fula has followed an independent development and is typologically distinct in many respects.

Dialectal relations — mutual intelligibility.

Fula is best understood as a dialect continuum: neighbouring varieties tend to be mutually intelligible, while varieties separated by long geographic distance may be only partially intelligible. Major named varieties include Pulaar (Senegambia, Mauritania), Pular (Guinea, Sierra Leone), and multiple Fulfulde varieties across Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad and the Central African Republic (e.g. Maasina Fulfulde, Adamawa Fulfulde). Most descriptions emphasize that there are ~20–30 principal dialects and many local varieties; speakers from neighbouring areas usually communicate without major difficulty, but comprehension decreases with geographic separation.

Origins, history and development

Scholars trace the early historic core of the Fulbe and their language to the westernmost Sudan/Senegambia area. Historical, linguistic and recent genetic work indicate a long history in the Middle Senegal Valley (Futa Toro) and Futa Jallon, with eastward expansions into the Sahel over the last millennium–one and a half millennia. Major historical processes that shaped the spread of Fula include pastoral migration, trade, and — especially in the 18th–19th centuries — Islamic reform movements and jihads (for example the Futa Toro, Futa Jallon, and the Sokoto and Massina movements) that spread Fulbe leadership, literacy (in Arabic script / Ajami) and Fula varieties across wide territories. Colonial-era borders and twentieth-century national language policies further affected distribution and literacy. Recent population-genomic studies and historical scholarship summarize migration from Futa Toro/Futa Jallon eastwards and assimilation with local populations during expansion. PMC+1

Where it is spoken and how many people speak it

Fula varieties are spoken across a wide arc from the Atlantic (Senegal, Mauritania, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau) east through Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, northern Benin, northern Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad and into parts of the Central African Republic, Sudan and beyond. It is used as a lingua franca in several countries (Senegal, Guinea, Gambia, Mali, Burkina Faso, parts of Nigeria and Cameroon, etc.). Modern speaker estimates vary by source; many references report roughly 30–37 million first-language speakers and substantially more if second-language users are included. (Different censuses and surveys give different totals; a single precise number is difficult because census questions, dialect boundaries and definitions of “speaker” vary.)

Writing systems and literacy

Fula has been written in several scripts:

-

Ajami (Arabic script): used for centuries by Islamic scholars and clerics in West Africa; important Ajami literatures in Fulfulde survive (poetry, religious treatises, letters). Famous 19th-century leaders and scholars used Ajami (and sometimes translated between Arabic and Fulfulde).

-

Latin orthography: standardized orthographies based on Latin script were developed in the 20th century (conferences such as Bamako 1966 influenced orthographic practices) and are now widespread in education, radio and print.

-

Adlam: a script invented in the late 1980s/1990s (by the Barry brothers in Guinea) specifically to write Fulfulde; it has seen rapid grassroots uptake in recent decades and is an important contemporary innovation for Fulfulde literacy and identity.

Literature and notable works

Fula literary traditions are rich and multimodal: oral epic, praise poetry, historical chronicles, Islamic learning in Ajami, and modern written literature.

-

Oral tradition and epic: centuries of oral epic and narrative performance (initiation stories, pastoral life narratives, praise songs and genealogies) are central; modern collectors such as Amadou Hampâté Bâ preserved and published many Fulbe oral texts (e.g. Kaïdara, other collected tales).

-

Ajami and Islamic poetry: leading 18th–19th-century reformers and scholars (for example, materials associated with Usman dan Fodio’s circle in the Sokoto Caliphate) produced religious poetry, didactic texts and letters in Fulfulde Ajami; these form a significant body of pre-colonial and early modern Fulfulde writing.

-

Modern prose and drama: 20th-century and contemporary authors (many bilingual in French/English and Fula) have produced novels, plays, translations and educational materials. Much classic Fulbe storytelling appears in French or English translations (e.g., works edited or recorded by Hampâté Bâ). Efforts in radio drama and school materials in Pulaar/Fulfulde expanded in the 20th century.

Grammar — major features

Typological outline. Fula is a suffixing language with a relatively rich nominal class (gender) system, agglutinative morphology on verbs, and flexible word order that is commonly described as SOV in many varieties but can show pragmatic reorderings. It uses an extensive system of nominal class markers (often called noun classes) that mark number, animacy and other grammatical distinctions; these classes are reflected in agreement on verbs, adjectives and possessives. Fula also distinguishes inclusive vs. exclusive “we” in its pronoun paradigms.

Noun class system. Depending on dialect, descriptions list roughly 20–26 noun classes (some dialects analyzed with slightly different counts). Class markers often appear as suffixes; they can function like articles and are central to concord across phrases.

Verbal morphology. Verbs are inflected for aspect, tense and polarity with suffixes and particles; serial constructions and aspectual auxiliaries are common. There is a well-known distinction between general/complete forms used in indirect discourse and relative/other verb forms used in narratives (see many field grammars).

Phonology — sketch

Phonological inventories vary by dialect, but several recurring features are:

-

Vowels: many varieties have a seven-vowel system (often transcribed /i ɪ e a o ʊ u/ or analyzed with an ATR contrast). Vowel length and vowel harmony (often ATR-based) are phonologically important in many dialects.

-

Consonants: rich consonant inventories include plain stops, prenasalized stops, fricatives, nasals and approximants; some varieties show labio-velars and phonemes conditioned by neighboring languages. Gemination and prenasalization are phonologically contrastive in many dialects.

-

Tone: unlike many Niger–Congo languages, Fula is often described as non-tonal (many sources emphasize that Fula varieties lack lexical tone, though prosodic pitch and intonational patterns exist).

Vocabulary and contact influence

Fula has a stable core lexicon with widespread borrowings from neighbouring language families as a result of long contact: Arabic (via Islam and scholarship, especially in Ajami contexts), Mande and Atlantic languages in the west, Chadic (e.g., Hausa) and Niger–Congo neighbours elsewhere. Modern vocabulary also includes borrowings from colonial languages (French, English, Portuguese in coastal areas) for modern concepts.

Example sentences (orthographic forms with translations)

Below are a few attested example sentences from grammars and teaching materials (orthography follows common Latin-based transcriptions used in descriptive sources):

-

Mi nanii o wujjii na’i faa keewi.

“I heard that he has stolen many cows.”

(Example illustrating indirect discourse / general complete verb forms.) -

Miɗo anndi.

“I know.” (miɗo = I (long subject form) + anndi = know). -

A jaaraama.

“Thank you.” (Pulaar / Pular / many Fulfulde varieties use A jaaraama or a jaraama). -

Miðo faala …

“I want …” (useful starter for requests).

(These examples are illustrative; exact pronunciation and minor morphological details vary by dialect.)

Short summary

Fula is a widely dispersed Senegambian (Atlantic) language continuum spoken by the Fulbe across a broad swathe of West and Central Africa. It has a long oral and Ajami literary history, a productive noun-class system, ATR-influenced vowel patterns, and many regional varieties that form a dialect continuum with variable levels of mutual intelligibility. Modern efforts in Latin orthography, radio and the Adlam script have broadened literacy and literary production in Fulfulde/Pulaar/Pular.

Mini-Phrasebook (Pulaar · Pular · Maasina Fulfulde)

Greetings

| English | Pulaar (Senegal/Mauritania) | Pular (Guinea/Sierra Leone) | Maasina Fulfulde (Mali) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hello / Peace | Jam waali / A jaaraama | A jaraama | Jam tun |

| How are you? | No mbaɗɗa? | No hiɓe waali? | No mbada? |

| I am fine. | Jam tan. | Jam tun. | Jam tan. |

| Thank you. | A jaaraama | A jaraama | A jaaraama |

Everyday Expressions

| English | Pulaar | Pular | Maasina Fulfulde |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | Eey | Eey | Eey |

| No | Alaa | Alaa | Alaa |

| Please | Mi yidiima | Mi yidiima | Mi yidiima |

| Excuse me / Sorry | Mi yettina | Mi yettinaa | Mi yottina |

| What is your name? | Innde maa holno? | Innde maa ko woni? | Innde ma holno? |

| My name is… | Innde am ko … | Innde am … | Innde am ko … |

Travel & Daily Needs

| English | Pulaar | Pular | Maasina Fulfulde |

|---|---|---|---|

| Where is … ? | Holto … ? | Hoto … ? | Holto … ? |

| I want water. | Miɗo yiɗi ndiyam. | Miɗo yiɗi ndiyam. | Miɗo yiɗi ndiyam. |

| Food | Leñol | Leñol | Leñol |

| Market | Suudu jaɓɓe | Luumo | Luumo |

| Friend | Gorko jeyaaɗo (male), Debbo jeyaaɗo (female) | Gorko jeyaado / Debbo jeyaado | Gorko jeyaado / Debbo jeyaado |

Useful Phrases

-

Pulaar (Senegal): Miɗo waɗi ɗum. — “I am doing it.”

-

Pular (Guinea): Miɗo anndi. — “I know.”

-

Maasina Fulfulde (Mali): On jaaraama. — “Thanks to you all.”

Leave your comments. What do you think?

To read more of our articles click on the links below.

- Afrikaans, click on this link.

- Albanian, click on this link.

- Amharic, click on this link.

- Arabic, click on this link

- Armenian, click on this link.

- Assamese, click on this link.

- Aymara, click on this link.

- Azeri,click on this link.

- Bambara, click on this link.

- Basque, click on this link.

- Belarusian, click on this link.

- Bengali, click on this link.

- Bosnian, click on this link.

- Bulgarian, click on this link.

- Catalan, click on this link.

- Cebuano, click on this link.

- Chewa, click on this link.

- Chinese, click on this link.

- Corsican, click on this link.

- Croatian, click on this link.

- Czech, click on this link.

- Danish, click on this link.

- Dhivehi, click on this link.

- Dogri, click on this link.

- Dutch, click on this link.

- Estonian, click on this link.

- Ewe, click on this link.

- Faroese, click on this link.

- Fijian, click on this link.

- Filipino, click on this link.

- Finnish, click on this link.

- Fon, click on this link.

- French, click on this link.

- Frisian, click on this link.