Ewe (Eʋegbe)

Ewe (autonym: Eʋegbe) is a Niger–Congo language of the Volta–Niger (formerly Kwa) branch, belonging to the Gbe cluster of closely related languages spoken in coastal West Africa. It is a tonal, analytic language with rich serial-verb constructions and a well-established literary and oral tradition.

Classification and related languages

Ewe is one major member of the Gbe languages (also written Gbé), a dialect-continuum that stretches from eastern Ghana through Togo and into Benin. Closely related languages include Gen (Mina), Fon, Aja, Adja, and several smaller Gbe varieties (Waci, Kpessi, Vo, etc.). Many of these varieties are mutually partially intelligible with Ewe; for example, varieties labelled Gen/Mina and many coastal Ewe dialects form a close continuum (often cited around ~80–90% intelligibility between some varieties). The Gbe cluster is normally treated as a subgroup of the Volta–Niger (Niger–Congo) family.

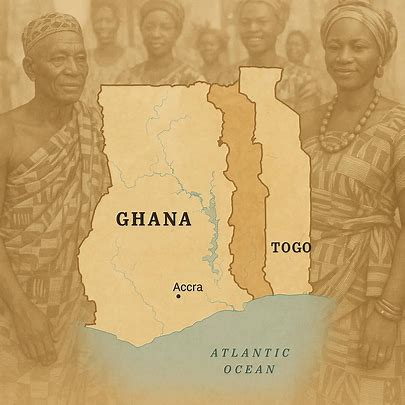

Numbers of speakers and geographic distribution

Ewe is spoken predominantly in southeastern Ghana and southern Togo, with smaller speaker populations in south-west Benin and diaspora communities abroad. Estimates of total first-language speakers vary by source and methodology (different counts include dialects and neighboring Gbe varieties), but standard references place the Ewe-speaking population in the low millions. Ethnologue and related surveys treat Ewe as a major language of wider communication in Ghana and Togo.

Origins, history and development

Oral and historical linguistic evidence places the ancestors of present-day Ewe speakers in a series of southward migrations in pre-modern times; one common account locates an early Tado homeland in the northern parts of present-day Togo, with later movements and kingdom formation between the 13th and 18th centuries. From the 18th century European coastal contact, trade, and missionary activity (notably by the Bremen and Basel missions) introduced literacy projects and the first translations of scripture into Ewe; these missionary efforts played a central role in developing an orthography and printed literature (including early Bible translations in the 19th century). Over the 20th century, Ewe became a language of education, media and literature in the region, while remaining part of a dialectal continuum with neighbouring Gbe varieties.

Dialects and mutual intelligibility

Ewe itself is often described as a dialect cluster. Major named dialects include Anlo (Aŋlɔ), Tongu (Tɔŋu), Avenor, Peki, Ho, Kpando and others; dialect differences may be local and gradual. Some neighboring Gbe varieties (e.g., Gen/Mina, Waci, Kpessi) are closely intelligible and sometimes considered dialects rather than distinct languages; Ethnologue and dialect studies discuss a dialect-continuum in which intelligibility ranges across the region.

Grammar (overview)

-

Basic word order: Ewe is typologically SVO (Subject–Verb–Object). Grammatical relations are largely signalled by word order and clitics rather than rich inflectional morphology.

-

Aspect and tense: Ewe is often described as aspect-prominent rather than tense-prominent; verbal morphology encodes aspectual distinctions, directional markers and modality.

-

Serial verb constructions: Ewe has an abundant system of serial verbs (multiple verbs forming a single complex predicate), used to express manner, direction, result, benefactive and other relations.

-

Pronouns and logophors: Ewe has a rich pronominal system, including logophoric pronouns — special pronouns used to report internal speech or attitudes of a source in indirect discourse (a well-known feature in Gbe languages).

-

Negation and clitics: Negation is frequently expressed with a combination of a negative prefix or particle on the verb and a clause-final element (different dialects and grammatical descriptions vary).

Phonology (overview)

-

Tone: Ewe is tonal. Most descriptions posit at least High and Mid/Low contrasts in many dialects; phonetic analyses discuss multiple tone registers and contour tones, with context-dependent tone lowering and downstep phenomena. Tone distinguishes lexical items and grammatical forms.

-

Vowels: Ewe has a rich vowel system with oral and nasal counterparts; many descriptions count seven to ten vowel qualities (with nasalization as a contrastive feature in every vowel).

-

Consonants: The consonant inventory includes labio-velar stops (e.g., kp, gb), contrastive fricatives such as ƒ vs. f, and a voiced apical post-alveolar stop ɖ vs dental d. Syllabic nasals occur and interact with tone.

Orthography and writing

Modern Ewe orthography uses a Latin-based alphabet adapted to represent Ewe’s phonemes (special letters and digraphs such as Ʋ/ʋ, ŋ, ɖ, gb, kp, ƒ). Tone marking is normally omitted in everyday orthography except where needed to disambiguate forms (some pedagogical or linguistic materials mark tone). Missionary translation work from the 19th century (and later revisions) established conventions that evolved into today’s orthography.

Vocabulary and sample sentences

Ewe vocabulary draws strongly on the oral literary tradition (songs, dirges, proverbs), daily life, and Bantu-adjacent cultural vocabulary. Below are a few useful lexical items and short example sentences (orthography follows standard published practice):

-

akpe — “thank you.”

-

meɖekuku — “please.”

Example sentences:

-

Kofi de suku. — “Kofi went to school.”

-

Kofi mede suku o. — “Kofi did not go to school.” (illustrates verbal negation pattern).

-

ekpɔ wò. — “He/She saw you.”

-

ekpɔ wo. — “He/She saw them.”

(contrast wò vs wo shows how tone or orthographic marking can disambiguate pronouns/objects).

These short examples illustrate tonal and clitic contrasts as well as basic SVO order and the negation pattern.

Literature, oral tradition and notable works

Ewe has an extensive oral literature — songs, proverbs, dirges, epic narratives and ritual recitations — that form a foundation for modern written literature. Missionary translation and early indigenous authors produced some of the first printed Ewe texts (Bible translations, catechisms, hymns).

Selected notable works and figures:

-

The Tragedy of Agbezuge (Amegbetɔa alo Agbezuge ƒe Ŋutinya), by Sam J. Obianim (published 1949), is commonly cited among early novels written in Ewe.

-

Ferdinand Kwasi Fiawoo’s play The Fifth Landing-Stage (and other dramatic works) draws on Ewe history and performance traditions and is an important early modern theatre piece in Ewe.

-

Bible translations and liturgical texts: nineteenth- and twentieth-century translations (Bremen Mission, later revisions) were central in creating a written corpus and teaching materials in Ewe; the Ewe New Testament editions and later complete Bibles have been important reference works.

-

Ewe influence on Anglophone poetry: Prominent Ghanaian poets such as Kofi Awoonor and Kofi Anyidoho drew heavily on Ewe oral genres (dirge, praise, ritual song) in their English-language poetry and scholarship; Awoonor also translated and analysed Ewe poetic forms. Their work helped bring Ewe oral forms to wider audiences and attest to the vitality of Ewe poetic practice.

Status and domains of use

Ewe functions as a language of everyday communication, local administration, radio broadcasting and education (especially in lower levels and non-formal education) in parts of Ghana and Togo. While national official status differs (English and French are the official languages of Ghana and Togo respectively), Ewe is recognised as a major national language and used in regional education, media and cultural life.

Study and documentation

Linguists have produced substantial descriptive work on Ewe: classic grammars and phonological analyses by Westermann, Ansre, Capo and more recent descriptive and theoretical work by scholars such as Felix Ameka, Alan Duthie and others. These studies have made Ewe one of the more thoroughly documented Gbe languages and a frequent subject in typological and tonal phonology research. Key topics in the literature include tone systems, serial verb constructions, logophoricity, and the semantics/pragmatics of oral genres.

📖 Short Folktale (Ewe with gloss and translation)

Text (Ewe):

Ŋutsu aɖe le ƒu si me. Eɖe be: “Meva doa kplɔkplɔkplɔ.”

Gloss (word by word):

-

Ŋutsu = man

-

aɖe = one / a certain

-

le = be.locative/progressive

-

ƒu = forest

-

si = REL (relative marker)

-

me = inside

-

Eɖe = he said

-

be = that/quotative

-

Me-va = 1SG-come

-

doa = walk

-

kplɔkplɔkplɔ = onomatopoeic “carefully, step by step”

Free translation:

“A man was in a forest. He said: ‘I will walk carefully, step by step.’”

This shows narrative style: verbs in serial sequence, quotative be, and ideophones like kplɔkplɔkplɔ adding vividness.

📑 Ewe Quick Grammar & Phrase Sheet

Phoneme Snapshot

-

Vowels: i e ɛ a o ɔ u (plus nasalised forms: ĩ ẽ ã õ ũ)

-

Consonants: p, b, t, d, ɖ, k, g, kp, gb, f, v, ƒ, ʋ, s, z, h, m, n, ŋ, l, r, w, y

-

Tone: high (´), mid (¯ often unmarked), low (`). Usually unmarked in everyday writing.

Pronouns

| Person | Independent | Subject prefix | Object |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1sg | me | me- | -me |

| 2sg | wò | wò- | -wò |

| 3sg | e | e- | -e |

| 1pl | mi | mi- | -mi |

| 2pl | miawo | mia- | -miawo |

| 3pl | wo | wo- | -wo |

Sentence Structure

-

Basic word order: Subject – Verb – Object

-

Negation: verb + o at clause end

-

Kofi mede suku o. → “Kofi did not go to school.”

-

-

Questions: often by intonation or with question words (e.g., ŋutsu si? “which man?”).

Common Phrases

-

Akpe — Thank you

-

Meɖekuku — Please

-

Woezɔ — Welcome

-

Ndi nɔvi. — Eat, my friend.

-

Ele agbe. — It is life / It’s fine. (greeting response)

Example Sentences

-

Me-dzo afi sia. → “I left this place.”

-

E-kpɔ wò. → “He saw you.”

-

Wo-va dome. → “They came inside.”

A video about the Ewe language:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sc7hdkdlVZg&list=PLz1jc8MbwqG7UQO_WJDkOtQFuUVVIxZ_J

To read all of our other articles on languages click on each of the links below.

- Afrikaans, click on this link.

- Albanian, click on this link.

- Amharic, click on this link.

- Arabic, click on this link

- Armenian, click on this link.

- Assamese, click on this link.

- Aymara, click on this link.

- Azeri,click on this link.

- Bambara, click on this link.

- Basque, click on this link.

- Belarusian, click on this link.

- Bengali, click on this link.

- Bosnian, click on this link.

- Bulgarian, click on this link.

- Catalan, click on this link.

- Cebuano, click on this link.

- Chewa, click on this link.

- Chinese, click on this link.

- Corsican, click on this link.

- Croatian, click on this link.

- Czech, click on this link.

- Danish, click on this link.

- Dhivehi, click on this link.

- Dogri, click on this link.

- Dutch, click on this link.

- Estonian, click on this link.

- Ewe, click on this link.