The Estonian Language

Classification

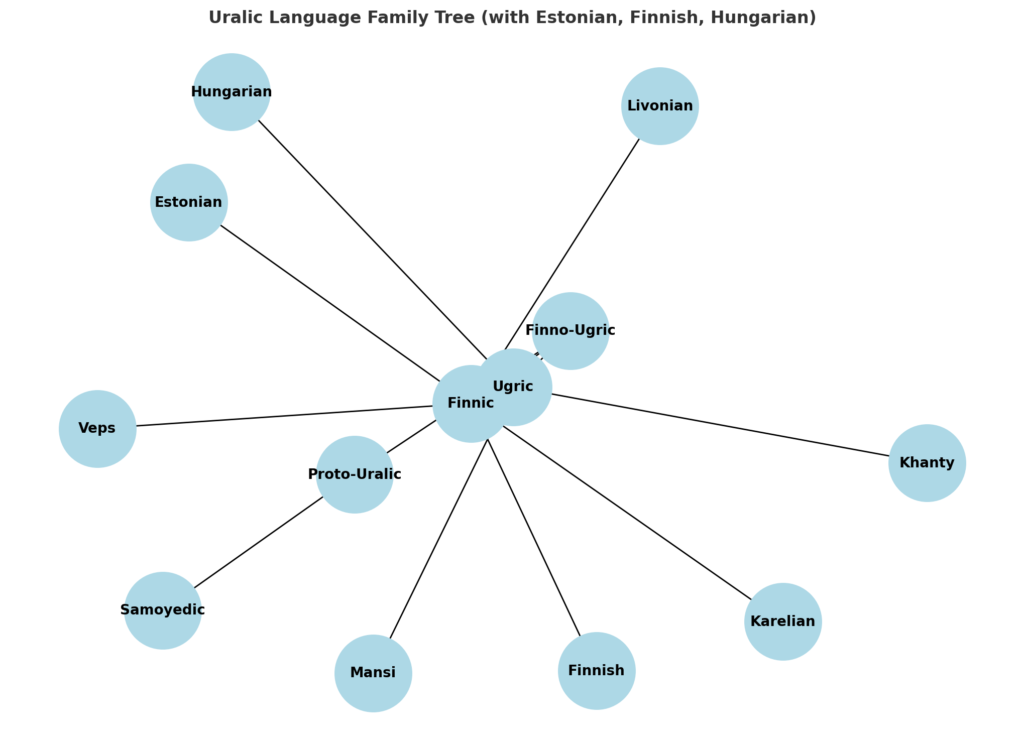

Estonian (Eesti keel) is a member of the Uralic language family, specifically belonging to the Finnic branch alongside Finnish, Karelian, Veps, Livonian, and others. Within this subgroup, Estonian is most closely related to Finnish, though centuries of separate development and extensive contact with Indo-European languages have led to notable divergences. Estonian and Finnish are partially mutually intelligible, especially in written form; however, comprehension is often limited in spoken conversation due to phonological, lexical, and syntactic differences. With more distant Finnic relatives such as Karelian, Votic, and Veps, mutual intelligibility is minimal, and with the now nearly extinct Livonian, only specialists can communicate effectively.

Geographic Distribution and Speakers

Estonian is the official language of Estonia, where it is spoken by approximately 1.1–1.2 million people as a first language. A further 200,000–300,000 speakers reside abroad, particularly in Finland, Sweden, Canada, the United States, and Russia. In total, around 1.3–1.5 million people are estimated to have proficiency in Estonian worldwide.

Historical Development

The Estonian language developed from Proto-Finnic, which itself split from Proto-Uralic several millennia ago. The earliest stages of Estonian saw heavy interaction with Baltic and Germanic languages, leading to widespread borrowing. By the 13th century, when the Northern Crusades brought Estonia under German, Danish, and later Swedish and Russian rule, Estonian was well established as the vernacular of the population.

The first known written words in Estonian appear in chronicles from the early 13th century, such as the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia. Systematic texts, including religious translations, emerged in the 16th and 17th centuries. The language underwent standardisation in the 19th century, during the Estonian national awakening, led by writers such as Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald and Johann Voldemar Jannsen. Following independence in 1918 and again after the restoration of independence in 1991, Estonian developed into a fully functional state language with a robust literary, scientific, and administrative tradition.

Literature

Estonian literature flourished particularly in the 19th century. The most famous early work is the national epic Kalevipoeg (1857–1861) by Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald, inspired by oral folklore and compiled in imitation of the Finnish Kalevala. Other significant authors include Lydia Koidula, a poet and playwright who helped establish modern Estonian literature, and Anton Hansen Tammsaare, whose monumental novel cycle Truth and Justice (Tõde ja õigus, 1926–1933) is considered a pinnacle of Estonian prose. In the 20th century, writers such as Jaan Kross and Jaan Kaplinski gained international recognition.

Grammar

Estonian is a highly inflected language with 14 grammatical cases, though it lacks grammatical gender and does not use articles. Case is used to mark syntactic and semantic relationships, e.g.:

-

maja (“house”, nominative)

-

majas (“in the house”, inessive)

-

majast (“from the house”, elative)

Verbs inflect for tense, mood, person, and number, though the personal system is less elaborate than in many Indo-European languages. For instance:

-

Ma loen raamatut. — “I am reading a book.”

-

Me lugesime raamatut. — “We read a book.”

Word order is relatively flexible, but subject–verb–object (SVO) is most common.

Phonology

Estonian phonology is characterised by three degrees of length (short, long, and “overlong”), which apply to both vowels and consonants. This quantity distinction is crucial to meaning:

-

lina [ˈlinɑ] — “linen”

-

linna [ˈlinːɑ] — “of the town”

-

linna [ˈlinːːɑ] — “to the town”

The vowel system consists of eight vowels, which can occur in both short and long forms. Consonant clusters are frequent, especially at morpheme boundaries. Stress generally falls on the first syllable.

Vocabulary

Estonian vocabulary is primarily Uralic in origin, but a substantial portion derives from centuries of contact with other language families. German (due to the Baltic German elite), Swedish, and Russian have been especially influential, while English borrowings dominate in the contemporary era. Examples include:

-

Native: silm (“eye”), kala (“fish”)

-

Germanic loan: aken (“window”, from Middle Low German)

-

Russian loan: kartul (“potato”)

-

English loan: internet (“internet”)

Example sentences:

-

Tere hommikust! — “Good morning!”

-

Kas sa räägid eesti keelt? — “Do you speak Estonian?”

-

Ilm on täna ilus. — “The weather is beautiful today.”

Estonian vocabulary and that of related languages such as Finnish and Hungarian.

Here is a comparative vocabulary table showing Estonian, Finnish (closest major relative), and Hungarian (a more distant Uralic cousin). It illustrates both similarities and divergences across the Uralic family:

Vocabulary Comparison

| English | Estonian | Finnish | Hungarian | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | vesi | vesi | víz | Clear cognates (shared Proto-Uralic root). |

| Fire | tuli | tuli | tűz | Cognates, though sound changes diverged. |

| Hand | käsi | käsi | kéz | Strong similarity between all three. |

| Eye | silm | silmä | szem | Estonian–Finnish closer; Hungarian diverged. |

| House | maja | maja (archaic; usually talo) | ház | Estonian–Finnish forms related; Hungarian differs. |

| Fish | kala | kala | hal | Clear cognates. |

| Sun | päike | aurinko | nap | Different roots; Estonian uses a Baltic loan (päike). |

| Day | päev | päivä | nap | Estonian–Finnish cognates; Hungarian unrelated. |

| Night | öö | yö | éj | Cognates across all three. |

| Language / Tongue | keel | kieli | nyelv | Estonian–Finnish cognates; Hungarian diverged. |

This table shows how Estonian and Finnish share a high degree of cognacy and parallel development, while Hungarian, despite being in the same Uralic family, has been more heavily reshaped by contact with Indo-European neighbours.

Here is a side-by-side comparison of example sentences in Estonian, Finnish, and Hungarian, showing both similarities in vocabulary (especially Estonian–Finnish) and the more distant structure of Hungarian:

Example Sentence Comparison

1. “I am reading a book.”

-

Estonian: Ma loen raamatut.

-

Finnish: Minä luen kirjaa.

-

Hungarian: Olvasok egy könyvet.

Notes: Estonian raamat and Finnish kirja differ (different borrowings), while Hungarian könyv is unrelated. Word order is similar, but Hungarian requires the article egy.

2. “The house is big.”

-

Estonian: Maja on suur.

-

Finnish: Talo on suuri.

-

Hungarian: A ház nagy.

Notes: Estonian maja ≈ Finnish maja/talo; Hungarian ház is cognate but looks more different. Hungarian requires the definite article a.

3. “Do you speak Estonian?”

-

Estonian: Kas sa räägid eesti keelt?

-

Finnish: Puhutko viroa?

-

Hungarian: Beszélsz észtül?

Notes: Finnish uses viro (“Estonia” in Finnish); Hungarian adds the suffix -ul for languages. Estonian case ending -t marks the object.

4. “We go to the city.”

-

Estonian: Me läheme linna.

-

Finnish: Menkäämme kaupunkiin.

-

Hungarian: Megyünk a városba.

Notes: All three show case endings: Estonian -na, Finnish -iin, Hungarian -ba mark direction “into”.

5. “The night is dark.”

-

Estonian: Öö on pime.

-

Finnish: Yö on pimeä.

-

Hungarian: Az éj sötét.

Notes: Cognates are clear: Estonian öö, Finnish yö, Hungarian éj all from Proto-Uralic.

These examples show:

-

Estonian–Finnish share grammar, vocabulary, and morphology, though not always identical.

-

Hungarian has diverged more in vocabulary and syntax, though deep Uralic roots remain visible in core words (e.g., öö–yö–éj).

Modern Status

Today, Estonian functions as the official state language of Estonia and as a symbol of national identity. It is protected and promoted by institutions such as the Institute of the Estonian Language (Eesti Keele Instituut). The language is used in government, education, media, and culture, and continues to evolve under the influence of globalisation and digital communication.

To read all of our other articles on languages click on each of the links below.

- Afrikaans, click on this link.

- Albanian, click on this link.

- Amharic, click on this link.

- Arabic, click on this link

- Armenian, click on this link.

- Assamese, click on this link.

- Aymara, click on this link.

- Azeri,click on this link.

- Bambara, click on this link.

- Basque, click on this link.

- Belarusian, click on this link.

- Bengali, click on this link.

- Bosnian, click on this link.

- Bulgarian, click on this link.

- Catalan, click on this link.

- Cebuano, click on this link.

- Chewa, click on this link.

- Chinese, click on this link.

- Corsican, click on this link.

- Croatian, click on this link.

- Czech, click on this link.

- Danish, click on this link.

- Dhivehi, click on this link.

- Dogri, click on this link.

- Dutch, click on this link.