Continental Celtic Languages

The term Continental Celtic refers to a group of Celtic languages historically spoken across mainland Europe, particularly before and during the early centuries of the first millennium CE. They form one half of the broader Celtic language family, the other being the Insular Celtic languages spoken in the British Isles. Like all Celtic languages, the Continental Celtic languages belong to the Indo-European language family, descending ultimately from Proto-Indo-European (PIE). Within the Indo-European family, they are part of the Italo-Celtic branch (a proposed grouping that suggests an early link to Italic languages such as Latin), though some scholars view the relationship more loosely and argue for parallel development rather than a shared, distinct proto-branch.

Origins and Development

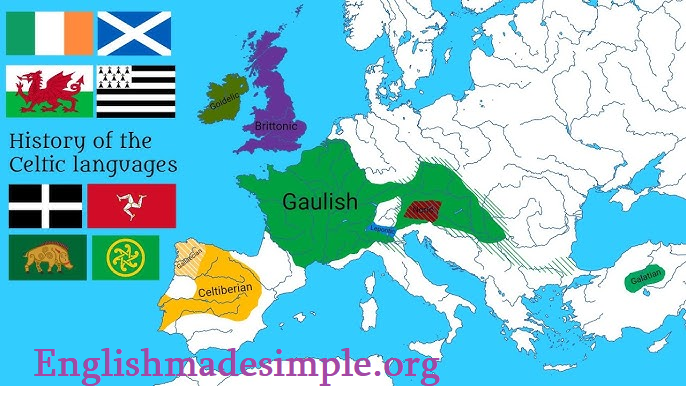

The origins of the Continental Celtic languages can be traced to Proto-Celtic, which emerged during the late Bronze Age, around the second millennium BCE, likely in an area near the upper Danube region or the foothills of the Alps. As Celtic-speaking peoples expanded across Europe during the early Iron Age, associated with the Hallstatt culture (c. 800–500 BCE) and later the more widely spread La Tène culture (c. 450 BCE to 1st century CE), Celtic speech diversified regionally. This diversification resulted in several distinct Continental Celtic languages, each associated with different tribal groupings and geographic regions.

By the 3rd century BCE, Celtic languages were spoken across a vast territory including Gaul (modern France and parts of Belgium, Switzerland, and Northern Italy), Iberia, Northern Italy, Central Europe, the Balkans, and even into Anatolia (in the form of Galatian). However, as these regions came under the political and cultural influence of the Roman Empire, Greek colonisation, and later Germanic expansion, the Celtic languages on the continent gradually declined.

Languages of the Continental Celtic Group

The Continental Celtic languages are generally divided into several recognised or hypothesised languages:

| Language | Region | Attestation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaulish | Gaul (France, Luxembourg, Switzerland, N. Italy, Belgium) | Inscriptions and classical references | The best-documented Continental Celtic language. |

| Lepontic | Northern Italy (Alpine / Cisalpine region) | Early inscriptions (6th c. BCE onward) | Sometimes considered the oldest attested Celtic language. |

| Celtiberian | Central and Northern Spain | Numerous inscriptions | Clearly Celtic; retains some very archaic features. |

| Galatian | Central Anatolia (Turkey) | Classical references and loanwords in Greek | Brought by migrating Celts in the 3rd c. BCE; poorly attested. |

| Noric | Austrian Alpine region | Very limited inscriptions | Often considered a dialect of Gaulish. |

Some additional names, such as Belgae Celtic, have been hypothesised based on tribal names or cultural evidence, but lack firm linguistic attestation.

Sub-Branches and Historical Development

The Continental Celtic languages can be grouped into two major sub-branches, though scholarly debate persists:

-

Celtic of the West / North-West (Gaulish and Lepontic)

These languages formed a broad dialect continuum across Gaul and the Alpine regions. Lepontic is sometimes regarded as an early, independent branch, though others classify it as early Cisalpine Gaulish. Gaulish later diversified into several local varieties (e.g., Transalpine Gaulish, Cisalpine Gaulish, and Noric Gaulish). -

Celtic of the Iberian Peninsula (Celtiberian)

Celtiberian developed partly in isolation from the more northern Celtic regions. It retains some older Proto-Celtic features abandoned in Gaulish, suggesting early differentiation, possibly before the full expansion of the La Tène culture. It also exhibits contact influence from Iberian languages.

Galatian, meanwhile, represents the result of long-distance migration: Celtic groups moving from Central Europe into Asia Minor in the 3rd century BCE. It probably resembled Gaulish closely but developed in intense contact with Greek and later Latin.

Decline and Extinction

The decline of Continental Celtic was closely linked with the spread of Latin under the Roman Empire. In Gaul, the process was gradual, taking several centuries, especially in rural areas. By the 5th century CE, Gaulish had largely disappeared, though some scholars argue that it may have survived in spoken form in isolated rural communities into the 7th century. In the Iberian Peninsula, Celtiberian declined more rapidly under Roman rule. Galatian is believed to have survived the longest, possibly until the 4th century CE, evidenced by references to Celtic-speaking populations in Anatolia by early Christian writers.

Differences and Similarities with Insular Celtic

The Continental Celtic and Insular Celtic languages share clear common ancestry, but they show significant divergence due to geographic separation and independent development. Insular Celtic is divided into two branches: Goidelic (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx) and Brittonic (Welsh, Cornish, Breton).

One of the most notable linguistic features dividing Celtic languages is the P-Celtic / Q-Celtic distinction:

| Feature | P-Celtic Languages | Q-Celtic Languages |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment of Proto-Celtic *kw | Becomes p | Retains k / kw |

| Example | *ekwos → *epos (horse) | *ekwos → *equos / ech (horse) |

In this classification, Gaulish and Brittonic are P-Celtic, while Celtiberian and Goidelic are Q-Celtic. This suggests that some divisions within Celtic predate the separation between Continental and Insular groups.

Table: Lexical and Grammatical Comparisons

| Feature | Continental Celtic (Gaulish/Celtiberian examples) | Insular Celtic (Welsh/Irish examples) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Word for ‘son’ | *mapos (Gaulish) | *map (Welsh), *mac (Irish) | Shows preservation of related roots. |

| Word for ‘horse’ | *epos (Gaulish, P-Celtic) / *equos (Celtiberian, Q-Celtic) | *ep (Welsh, P-Celtic) / *ech (Old Irish, Q-Celtic) | Reflects P- and Q-Celtic split. |

| Gender system | Masculine, feminine, neuter | Masculine and feminine (neuter largely lost) | Insular Celtic lost neuter gender early. |

| Verb syntax | Generally SOV or SVO | Predominantly VSO | A major syntactic difference. |

| Mutation systems | Minimal evidence | Extensive initial consonant mutation | Mutation likely developed later in Insular Celtic. |

| Case system | Fully maintained Indo-European cases | Gradual case reduction in Goidelic; absent in Brittonic | Continental Celtic is more archaic. |

Comparative Table of Major Continental Celtic Languages

| Language | Script(s) Used | Approximate Period | Distinctive Features | Degree of Documentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaulish | Greek script (Southern Gaul), Latin script | 3rd c. BCE – 5th c. CE | P-Celtic features; inscriptions, personal names | Relatively well-attested |

| Lepontic | Variant of Etruscan-derived alphabet | 6th c. BCE – 1st c. CE | Earliest written Celtic; debated relation to Gaulish | Moderately attested |

| Celtiberian | Celtiberian semi-syllabary, Latin script | 2nd c. BCE – 1st c. CE | Q-Celtic features; archaic morphology | Well-attested epigraphically |

| Galatian | Written in Greek script (loanwords) | 3rd c. BCE – 4th c. CE | Close to Gaulish; heavy Greek influence | Poorly attested |

| Noric | Latin script (few inscriptions) | 1st c. BCE – 2nd c. CE | Likely Gaulish variant | Very limited evidence |

Legacy

Though the Continental Celtic languages are extinct, they have left enduring traces:

-

Place names: For example, Paris (from the Parisii tribe) and Lugdunum (modern Lyon).

-

Loanwords in Latin and later Romance languages: e.g., carrus (“wagon”) → French char, English car.

-

Cultural memory and archaeology: The artistic motifs of La Tène Celtic art remain highly influential.

The surviving Insular Celtic languages, particularly Welsh and Irish, preserve many echoes of earlier Celtic linguistic structures, enabling scholars to reconstruct some aspects of Continental Celtic speech.

Conclusion

The Continental Celtic languages form a significant but now extinct branch of the Celtic linguistic heritage. Emerging from Proto-Celtic and spreading widely across Iron Age Europe, they reflected the cultural dynamism and mobility of Celtic-speaking peoples. Their decline was gradual, ultimately driven by political and cultural assimilation under the Roman Empire and later linguistic pressures. Nevertheless, through inscriptions, toponyms, and comparative linguistic analysis, the legacy of Continental Celtic remains crucial to understanding the early linguistic history of Europe and the development of the Celtic family as a whole.