Breton (Language) — Family, History, Structure, and Comparative Profile

Overview

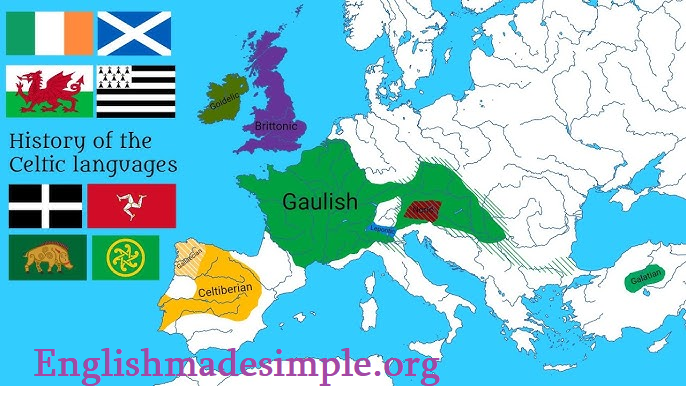

Breton (brezhoneg) is a Celtic language spoken in Brittany (Breizh), the western peninsula of modern-day France. It belongs to the Brythonic (or Brittonic) branch of the Insular Celtic subgroup within the wider Celtic family, itself a member of the Indo-European language family. Closest relatives are Welsh (Cymraeg) and Cornish (Kernewek). More distantly, Breton is related to the Goidelic Celtic languages—Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx—and, at a far remove, to the other Indo-European branches such as Germanic (including English), Romance (French, Spanish), Slavic, Indo-Iranian, and so forth.

Although often called “a language,” Breton is usefully discussed as part of a family cluster—the Brythonic trio—because most of its structural traits are best understood in relation to Welsh and Cornish. What follows sets Breton in its genealogical context, summarises its history in Brittany, explains its relationship with English, and outlines its grammar with clear examples, before comparing it systematically with its sister languages.

Genetic Classification

Indo-European

└── Celtic

├── Continental Celtic (extinct: Gaulish, Lepontic, etc.)

└── Insular Celtic

├── Goidelic (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx)

└── Brythonic / Brittonic

├── Welsh (Cymraeg)

├── Cornish (Kernewek)

└── Breton (Brezhoneg)

Key points

-

Breton is Brythonic, not Goidelic.

-

It shares a core typological profile with Welsh and Cornish: initial consonant mutation, a tendency toward VSO (verb–subject–object) order, widespread periphrasis with verbal nouns, inflected prepositions, and rich deictic (this/that) systems.

-

It is an Insular Celtic language in structure, despite being spoken on the European mainland; historically, it was transplanted there from Britain.

Origins, Migrations, and Early Development

From Britain to Armorica (5th–7th centuries CE)

Breton’s ancestors were spoken in south-western Britain. During late Roman and early post-Roman times (approximately the 5th to 7th centuries CE), waves of Brittonic-speaking migrants crossed the Channel to Armorica, the region that later came to be called Brittany. This movement created new, linguistically Brythonic communities on the continent and permanently separated Breton from the developing Welsh and Cornish back in Britain.

Medieval consolidation (8th–12th centuries)

In Brittany, the language developed through contact with Latin (via the Church) and Gallo-Romance varieties (precursors of French and Gallo). Old Breton texts (glosses, charters, and personal names) reveal a Brythonic system already exhibiting mutation and verb-initial syntax. Lexically, Breton adopted ecclesiastical and administrative vocabulary from Latin, while preserving an indigenous Celtic core.

Later medieval and early modern periods (13th–17th centuries)

Middle Breton (c. 12th–17th centuries) saw a blossoming of literature (poetry, miracle plays, religious prose). Orthographic conventions were debated and fluid; scribes variously mirrored French spelling habits or devised Breton-specific solutions. Throughout, dialectal differentiation deepened as regional centres (Léon, Trégor, Cornouaille, Vannes) cultivated distinct features.

Modern Breton and standardisation (18th century–present)

The French state gradually expanded schooling in French and discouraged regional languages. Breton remained vigorous in the western rural areas into the 19th and early 20th centuries, but urbanisation and national education accelerated shift to French. From the late 20th century, revitalisation gathered pace: standard orthographies (notably Peurunvan “unified spelling”), Diwan immersion schools, and a cultural renaissance in music and media. Today, Breton is a regional minority language in France with active community, educational, and publishing networks.

Sub-branches and Internal Diversity

Breton’s “sub-branches” are best understood as major dialect areas:

-

Kerneveg (Cornouaille)

-

Leoneg (Léon)

-

Tregerieg (Trégor)

-

Gwenedeg (Vannetais)

KLT (Kernev–Léon–Trégor) varieties share many features and underlie much of the Peurunvan standard. Gwenedeg is more distinct phonologically (e.g., stress patterns, vowel qualities) and morphosyntactically, reflecting a long separate evolution in the south-east of Brittany.

How they emerged

-

Geography: peninsular valleys and historic diocesan boundaries encouraged regional norms.

-

Contact: differing degrees of contact with Gallo (Romance) and French created lexical and phonological divergence.

-

Literacy centres: medieval scriptoria and later printing hubs reinforced regional orthographic habits.

Breton and English: Historical Threads and Modern Realities

Deep relationship (Indo-European cousins)

English and Breton share Indo-European ancestry, but diverged early: English is Germanic, Breton Celtic. Consequently, core grammar differs sharply, but distant cognates can sometimes be teased out in basic vocabulary (e.g., number words and kin terms through Proto-Indo-European).

Channel contacts

There were maritime ties between Brittany and south-west Britain for over a millennium (trade, fishing, migration). Cornish and Breton kept particularly close links; English–Breton contact was spottier and mostly mediated through French or Gallo.

English in modern Brittany

In contemporary France, English functions as an international lingua franca taught in schools; Breton functions as a regional heritage language. The interplay is asymmetric: French dominates public life; Breton occupies community, cultural, and educational spaces; English appears primarily in education, tourism, and media. Nonetheless, the revivalist scene often uses English‐language platforms to promote Breton music and festivals, and cross-Celtic events foster English-medium communication among Celtic-language advocates.

English loanwords and calques

Modern Breton—like most European languages—has absorbed international English loanwords (often via French), particularly in technology and culture. Historically, English loans are scarce relative to French and Latin loans.

Key Grammatical Features of Breton (with Examples)

Conventions below use standard Peurunvan spelling. Examples give Breton, literal gloss, and natural English translation.

1) Articles (Definite and Indefinite)

-

Definite article: ar / al / an

-

Distribution is phonologically conditioned:

-

ar before most consonants: ar mab — “the son”

-

al before l: al lagad — “the eye”

-

an before vowels (and some contexts): an den — “the person”

-

-

-

Indefinite article: ur (sg., meaning “a/one”):

-

Ur c’hi — “a dog”

-

Plural indefiniteness is usually zero or expressed periphrastically.

-

Note on mutation: Articles can trigger initial consonant mutation on the following noun in specific contexts.

2) Demonstratives

Breton places deictic particles after the noun (and article), giving a three-way proximity contrast:

-

-mañ = “this (near me)”

-

-se = “that (near you)”

-

-hont = “that (over there, yonder)”

Examples

-

an ti-mañ — “this house”

-

ar plac’h-se — “that girl (near you)”

-

an ti-hont — “that house over there”

Independent demonstrative pronouns exist too (e.g., hemañ “this one (m.)”, homañ “this one (f.)”, hennezh “that one (m.)”), used for stand-alone reference.

3) Word Order and Clause Particles

Canonical order in finite clauses is often VSO (verb–subject–object), mediated by clausal particles:

-

a marks many affirmative relative/focus clauses.

-

ne… ket marks negation.

Examples

-

Affirmative focus:

Gwelan me ar mor.

see-1SG I the sea

“I see the sea.”Or with the focus particle:

Me a gwel ar mor.

I PRT see the sea

“It is I who see the sea / I do see the sea.” -

Neutral declarative (colloquial subject-initial is also common):

Ar mor a zo brav hiziv.

the sea PRT is beautiful today

“The sea is beautiful today.” -

Negation:

Ne gwelan ket ar mor.

NEG see-1SG not the sea

“I do not see the sea.”

Breton also uses clefting, fronting, and topic–comment strategies typical of Insular Celtic.

4) Verbs, Verbal Nouns, and Periphrasis

Breton has synthetic verb forms (with endings) and periphrastic constructions built on the verbal noun.

-

Progressive: emaon o + verbal noun

Emaon o vont.

be-1SG.PROG at go.VN

“I am going.” -

Prospective/future-like (with mont da “go to”):

Mont a ran da lenn.

go PRT do-1SG to read.VN

“I’m going to read.” -

Perfect/experiential (with bezañ “to be” + participial/periphrastic patterns; also kaout “to have” in some registers).

5) Conjugation (Indicative Snapshot)

Using gwelet “to see” (stem gwel-) in a simple present-type pattern:

| Person | Breton (affirmative focus) | Gloss | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 sg | Me a gwelan | I PRT see-1SG | I see |

| 2 sg | Te a welez | you PRT see-2SG | you see |

| 3 sg | Eñ/Hi a wel | he/she PRT see-3SG | he/she sees |

| 1 pl | Ni a welomp | we PRT see-1PL | we see |

| 2 pl | C’hwi a welit | you.PRT see-2PL | you see |

| 3 pl | Int a welont | they PRT see-3PL | they see |

Negation inserts ne… ket and uses the same endings:

-

Ne whelan ket. (lenition/soft mutation after ne) — “I don’t see.”

Mutation patterns vary with particles, pronouns, and prepositions.

6) Tense–Aspect–Mood (Overview with Examples)

Breton distinguishes simple (synthetic) and periphrastic TAM constructions; usage varies by register (literary vs. colloquial).

-

Present / Habitual:

Me a gwelan alies. — “I (usually) see (it) often.” -

Progressive (ongoing):

Emaon o lenn. — “I am reading.” -

Imperfect (past habitual/continuous):

Me a wele bemdez. — “I used to see (it) every day.” -

Preterite (simple past, literary/learned):

Me gwelis. — “I saw.” (more common in formal or written style) -

Periphrastic Past / Perfect-like (colloquial):

’M eus gwelet — “I have seen / I saw.” (kaout “to have” + verbal noun/participle patterns) -

Future:

Synthetic: Me a welin — “I will see.”

Periphrastic (prospective): Me a zo o vont da welet — “I am going to see.” -

Conditional:

Me gwelefen — “I would see.” -

Subjunctive/relative constructions occur mainly in embedded clauses, often cued by complementisers and particles.

7) Initial Consonant Mutation (Sketch)

Breton (like Welsh and Cornish) modifies a word’s initial consonant in specific grammatical environments:

-

Soft mutation (lenition): p→b, t→d, k→g, m→v, gw→w, etc.

Triggered e.g. by certain particles, possessives (va “my”), numerals, and prepositions. -

Aspirate/fricative and other patterns exist (distribution is system-specific and dialect-sensitive).

Example

-

ti “house” → va di “my house” (after va “my”, t lenites to d).

8) Inflected Prepositions

Prepositions fuse with pronominal objects:

-

gant “with” → ganin “with me”, ganit “with you (sg.)”, gantañ “with him”, ganti “with her”, ganimp “with us”, ganoc’h “with you (pl.)”, ganto “with them”.

Example

-

Deuit ganin — “Come with me.”

Similarities and Differences within Brythonic

Breton’s nearest relatives are Welsh and Cornish. All three share key Celtic traits (mutation, V-initial patterns, verbal nouns, inflected prepositions). Yet they differ in articles, phonology, orthography, and some morphosyntax.

Quick Lexical Glimpses

-

“one–five”:

Breton: unan, daou/div (m/f), tri/teir, pevar/peder, pemp

Welsh: un, dau/dwy, tri/tair, pedwar/pedair, pump

Cornish: onan, dew/diw, tri/teyr, peswar/pedyr, pymp -

“house”: Breton ti, Welsh tŷ, Cornish chi

-

“man/person”: Breton den, Welsh dyn, Cornish den

These cognates illustrate shared Brythonic inheritance with predictable sound correspondences (e.g., Breton t ≈ Welsh circumflexed tŷ outcome, Cornish ch for earlier t in some contexts).

Comparative Table: Selected Lexical & Grammatical Features

| Feature | Breton (Brezhoneg) | Welsh (Cymraeg) | Cornish (Kernewek) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Brythonic Celtic | Brythonic Celtic | Brythonic Celtic | All Indo-European |

| Definite article | ar / al / an | y / yr / ’r | an | Phonologically conditioned allomorphs in B & W |

| Indefinite article | ur (sg.; ‘a/one’) | none (uses un numeral) | unn (modern usage) | Breton/Cornish grammaticalise the numeral more like an article |

| Demonstratives | postposed: -mañ / -se / -hont | postposed: -ma / -na | postposed: -ma / -na | Three-way deictics clearest in Breton |

| Typical word order | VSO (S-initial common too) | VSO | VSO | All permit topicalisation/clefting |

| Negation | ne … ket | ddim / nid / ddim (varied patterns) | ny / na … (historical; modern usage varies) | Breton’s ket is a robust postverbal negator |

| Verbal noun | yes: o + VN progressive | yes: yn + VN | yes: ow + VN | Shared Insular Celtic hallmark |

| Inflected preps | gant → ganin (“with me”) | gyda → gyda fi (analytical), many inflected historically (gennyf) | gans → genes | Modern Welsh is more analytical colloquially; literary forms still inflected |

| Mutation types | soft + others | soft, nasal, aspirate | soft (lenition) + others | Triggers differ language-internally |

| Numerals (2–4) gender | daou/div, tri/teir, pevar/peder | dau/dwy, tri/tair, pedwar/pedair | dew/diw, tri/teyr, peswar/pedyr | Gender agreement retained |

| Plurals | suffixal & internal changes | as in Breton (varied) | as in Breton (varied) | Rich plural morphology across the three |

Sample Breton Grammar in Context

Articles + Noun + Demonstrative

-

An den-mañ a zeu.

the person-THIS PRT come

“This person is coming.”

Negation and Mutation

-

Ne welan ket an ti-mañ.

NEG see-1SG not the house-THIS

“I don’t see this house.”

Progressive with Verbal Noun

-

Emaomp o labourat bremañ.

be-1PL.PROG at work.VN now

“We are working now.”

Inflected Preposition

-

Deuit ganin d’ar vro.

come with-1SG to-the country

“Come with me to the country.”

Future (synthetic)

-

Me a welin ar mor warc’hoazh.

I PRT see-FUT.1SG the sea tomorrow

“I will see the sea tomorrow.”

Relationship with French in Modern France

-

Sociolinguistic status: Breton is a regional language with limited official support compared with French, but recognised in cultural policies and regional signage.

-

Education: Immersion schools (often under the Diwan network) and bilingual streams in public/private systems teach through or alongside Breton.

-

Media & culture: radio shows, music (fest-noz traditions), festivals, and a modest publishing industry maintain public presence.

-

Language shift & revitalisation: The shift to French across the 20th century severely reduced intergenerational transmission; today, revival focuses on schooling, early-years immersion, and increased visibility in public life.

Further Structural Notes (Concise)

-

Noun phrase: Possessives precede the noun and trigger mutation (va zi “my house”; he zad “her father” with spirantisation vs. e dad “his father” with soft mutation).

-

Adjectives: typically postnominal; may trigger or undergo mutation depending on context.

-

Prepositions: many compound forms (e-barzh “in”, e-kerzh “during”, e-tre “between”).

-

Numbers: elaborate systems for counting people/objects, with gender agreements for 2–4 and traditional vigesimal patterns in some registers.

-

Orthographies: Peurunvan is widely used; Skolveurieg (University orthography) and ETR (reformed Trégorrois) exist historically/regionally.

-

Register: Spoken Breton ranges from colloquial KLT patterns to Gwenedeg-rich local speech; formal writing can be more synthetic and literary.

Relationship to English: Similarities and Contrasts

Similarities

-

Both are Indo-European and display analytic tendencies in modern usage (periphrastic tenses, fixed SVO in English vs. Breton’s growing tolerance for S-initial orders in colloquial speech).

-

Shared international vocabulary (often through French/Latin) in modern times: technology, culture, administration.

Contrasts

-

Breton preserves Insular Celtic hallmarks absent in English: initial consonant mutations, inflected prepositions, postposed demonstratives, and a historically VSO default.

-

English lost grammatical gender in nouns; Breton retains gender (masc./fem.) with effects on numerals and mutation.

Lexical pathways into English

-

English contains a few Breton antiquarian terms such as menhir (“long stone”) and dolmen (often analysed as “table stone”), popularised in archaeology—illustrating cultural rather than structural contact.

Summary

Breton is a Brythonic Celtic language transplanted from Britain to Armorica in late antiquity. It has evolved on the European mainland while maintaining a deep structural kinship with Welsh and Cornish: mutation, VSO tendencies, verbal nouns, and inflected prepositions define much of its grammar. Internally, it comprises several dialect areas—Kerneveg, Leoneg, Tregerieg, Gwenedeg—whose distinctions reflect geography, contact, and literary centres.

Breton’s relationship with English is primarily genealogical (distant cousins) and cultural, rather than one of intense structural contact; French has been the dominant adstratum. In modern France, Breton is a minority language undergoing revitalisation, with immersion schooling, media, and cultural initiatives sustaining its presence.

From articles ar/ al/ an and demonstratives -mañ/-se/-hont, to ne … ket negation and o + verbal-noun progressives, Breton offers a compact yet distinctive Celtic grammatical system. Its parallels with Welsh and Cornish are striking, while the divergences—articles, mutation triggers, and phonology—reveal centuries of separate development on either side of the Channel.

Worked Breton Examples (One-glance Recap)

-

Definite/Indefinite: ar merc’h “the girl”; ur c’hi “a dog”

-

Demonstratives: an ti-mañ “this house”; ar gêr-se “that town”; an ti-hont “that house yonder”

-

VSO: Glev a ra ar vamm. — “The mother hears.”

-

Negation: Ne glev ket ar vamm. — “The mother does not hear.”

-

Progressive: Emaon o skrivañ. — “I am writing.”

-

Inflected prep: Ganti e tleomp mont. — “With her we must go.”

Comparative Snapshot (Vocabulary)

| Gloss | Breton | Welsh | Cornish |

|---|---|---|---|

| house | ti | tŷ | chi |

| man/person | den | dyn | den |

| woman | maouez | gwraig | benyn/benenes |

| child | bugel | plentyn | flogh |

| sea | mor | môr | mor |

| day | deiz | dydd | dedh |

(Orthographic differences reflect sound changes and conventions across the languages.)

Closing Note

For learners and enthusiasts, Breton rewards attention with a coherent, elegant grammar and a living cultural tradition. Understanding its place within Brythonic and Indo-European helps situate its unique features—mutation, demonstratives, verbal nouns—while comparison with Welsh and Cornish illuminates both the shared Celtic heritage and the distinctive Breton trajectory on the continent.