Cornish (Kernewek)

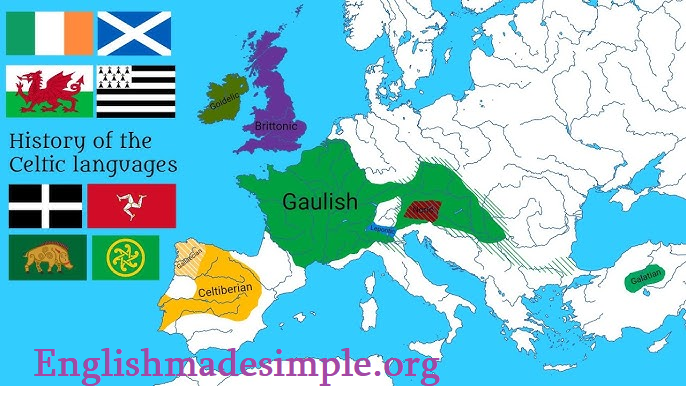

Cornish (Kernewek) is a Celtic language originating in Cornwall, the far south-west of Great Britain. It belongs to the Brythonic (Brittonic) branch of the Insular Celtic languages within the Indo-European family. Its closest relatives are Welsh and Breton; more distantly it is related to the Goidelic branch (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx). After a period of severe decline and dormancy by the late eighteenth century, Cornish underwent a modern revival and is today used in education, public signage, media, and cultural life in Cornwall.

Language family and related branches

A simple way to situate Cornish is with a family-tree sketch:

└── Celtic

├── Continental Celtic (extinct; e.g., Gaulish, Lepontic)

└── Insular Celtic

├── Goidelic (Gaelic)

│ ├── Irish

│ ├── Scottish Gaelic

│ └── Manx

└── Brythonic (Brittonic)

├── Welsh

├── Breton

└── Cornish

The Brythonic branch descends from the speech of the Britons of Roman and sub-Roman Britain. Breton emerged through migration from Britain to Armorica (Brittany) in Late Antiquity; Welsh developed in Wales; Cornish developed in Cornwall. The three share substantial grammar and vocabulary (e.g., penn ‘head’, dour/dowr ‘water’, da ‘good’), and all exhibit initial consonant mutation and a preference for verb-initial clause patterns in certain contexts.

Origins, history, and development

Prehistory to early medieval

Cornish developed from Common Brittonic, spoken across much of Britain in the Iron Age and Roman eras. With the spread of Anglo-Saxon dialects east of the River Tamar, Cornwall remained a stronghold of Brittonic speech. By c. 800–1000 CE, a distinct Old Cornish can be inferred from place-names and glosses.

Middle Cornish (c. 1200–1600)

The best-known early literature is Middle Cornish, preserved in verse dramas and religious plays such as Origo Mundi and Pascon agan Arluth (The Passion of Our Lord). This period shows a confident literary culture, with orthography not yet standardised but recognisably Cornish and distinct from Welsh and Breton.

Late Cornish (c. 1600–1800)

From the sixteenth century, English gained dominance due to administrative, economic, and social pressures. Cornish retreated westwards, remaining longest in Penwith and the far west. The last traditional native speakers are usually placed in the late eighteenth century (a symbolic name often mentioned is Dolly Pentreath, d. 1777, though conversational knowledge persisted for some neighbours and descendants).

Revival (from 1900)

A linguistic revival began in the early twentieth century. Henry Jenner’s Handbook of the Cornish Language (1904) introduced learners to reconstructed Cornish; R. Morton Nance later proposed Unified Cornish. In the late twentieth century various standardisation efforts arose—Kernewek Kemmyn, Unified Cornish Revised, and Late/Modern Cornish—reflecting different priorities (phonology, historical fidelity, or late-stage usage). To support education and public use, stakeholders agreed a compromise orthography, the Standard Written Form (SWF) (2008), widely used for signage, schools, and examinations. Cornish has recognition under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in the UK, and there is an active ecosystem of classes, children’s materials, radio segments, and cultural events.

Diachronic development and sub-branches within Cornish

It is conventional to speak of Old, Middle, and Late Cornish stages:

↓

Middle Cornish (c.1200–1600)

↓

Late Cornish (c.1600–1800)

↓

Revived Cornish (20th–21st c.)

-

Old Cornish is sparsely attested (glosses, names). Phonologically, it shares the Brythonic shift kw → p (cf. Latin equus vs. Welsh/Cornish epos/p reflexes) that distinguishes Brythonic from Goidelic.

-

Middle Cornish shows rich verbal morphology, systematic initial mutations, and the use of verbal nouns. Orthography is variable but literary.

-

Late Cornish exhibits English influence (loanwords, syntax) and reduced inflection in some texts, but retains core Brythonic structure (mutations, preposition inflection, periphrasis).

-

Revived Cornish blends evidence from all periods, regularising spelling in the SWF and systematising grammar for modern use.

Structural overview of Cornish grammar

Cornish grammar is recognisably Brythonic: no indefinite article, a single definite article, demonstratives post-posed to the noun phrase, initial consonant mutation, rich prepositional inflection, and a verb–subject–object (VSO) clause pattern in many main clauses.

Articles

-

Definite article: an ‘the’.

-

Triggers soft mutation of feminine singular nouns (and in some contexts of adjectives):

-

an venyn ‘the woman’ (from benyn)

-

an den ‘the man’ (masculine: no mutation of den)

-

-

-

Indefinite article: none (like Welsh and Breton). If needed, unn ‘one’ can express indefiniteness or emphasis.

-

Den a dheuth. ‘A man came.’

-

Unn lyver vygh ow kerri. ‘I am carrying one book.’

-

Demonstrative pronouns and determiners

Demonstratives follow the noun (with the article), using ma ‘this’ and na ‘that’:

-

an den ma ‘this man’

-

an chi na ‘that house’

-

Stand-alone pronouns include forms like hema ‘this (one)’ and henna ‘that (one)’.

Word order and clause structure

Canonical main-clause order is often VSO, especially with the affirmative particle a (and in relatives and focus constructions). With certain particles (negative, interrogative, progressive), order adjusts, but subject-verb inversion or fronting is common.

-

Neutral/affirmative:

-

Yth esa an maw ow studhya. ‘The boy was studying.’

-

Gwelav vy an chi. ‘I see the house.’

-

-

With particle a (literary/neutral link):

-

A wel vy an chi. ‘I (do) see the house.’

-

-

Focused object:

-

An lyver a wrug hi gasa gans an das. ‘It was the book she left with the father.’

-

Initial consonant mutation

Cornish uses initial consonant mutation conditioned by syntax, particles, and certain prepositions/possessives. A simplified snapshot:

-

Soft mutation (lenition):

-

p → b (pysk → bysk), t → d, k → g, b → v, d → dh, g → Ø (often drops), m → v, gw → w, s often to h in historical orthographies (varies in SWF contexts).

-

-

Triggers include: feminine singular after an, possessive ow ‘my’, the verbal particle a, and negative particles.

Verbs, conjugation, and tense/aspect

Cornish has both synthetic (inflected) and periphrastic verb forms, with the verbal noun central to progressive and infinitival constructions.

The verb bos ‘to be’ (irregular)

Present (common revived forms):

-

Yth esov vy ‘I am’

-

Yth os jy ‘thou art’ (familiar; often yth os ta)

-

Yth yw ev/hi ‘he/she is’

-

Yth eson ni ‘we are’

-

Yth esowgh hwi ‘you (pl.) are’

-

Yth yns i ‘they are’

Examples:

-

Yth yw hemma chi nowyth. ‘This is a new house.’

-

Yth eson ni ow kerdhes. ‘We are walking.’

Periphrastic progressive with ow + verbal noun

-

Yth esov vy ow studhya. ‘I am studying.’

-

Yth yw hi ow kwri. ‘She is making/doing.’

(NB: ow causes soft mutation of many initial consonants in the verb-noun.)

Present/future with particle a or without

A single present/future stem often serves both time-references, with context or adverbs clarifying:

-

(A) gwerthav vy bara demain. ‘I (will) sell bread tomorrow.’

-

Gwerthav vy bara pub dydh. ‘I sell bread every day.’

Preterite (simple past)

-

Wrug vy gweles an den. / Gwelis vy an den. ‘I saw the man.’

Both periphrastic (wrug + VN or inflected) and synthetic forms appear in revived usage.

Imperfect/past habitual

-

Yth esa hi ow kewsel. ‘She was talking.’

-

Kewselly hi yn fenowgh. ‘She used to speak often.’

Perfect and pluperfect

-

Often formed with bos + past participle or periphrasis; revived usage varies:

-

Yth esov vy gwelyes. ‘I have seen.’ (many write simply Gwelis for perfect sense, with adverbs)

-

Subjunctive and modal nuances

Cornish retains a subjunctive in some set phrases and after certain conjunctions, though in modern use periphrastic strategies with particles are common. Modal meaning uses adverbs and modal verbs (e.g., galloes ‘can’).

Imperatives

-

Singular: Gwrug! ‘Do!’ / Kewsel! ‘Speak!’

-

Plural/polite: Kewselowgh! / periphrastic politeness with particles is frequent.

Negation and interrogation

-

Negative particles: ny/na (often with mutation).

-

Ny welav vy. ‘I do not see.’

-

Ny wre vy mos. ‘I will not go.’

-

-

Questions commonly use verb-initial order or an interrogative particle:

-

A weli jy? ‘Do you see (it)?’

-

Piw yw hemma? ‘Who is this?’

-

Noun phrase and agreement

-

Gender: masculine/feminine; certain adjectives agree or mutate after feminine singular.

-

Number: regular plurals plus collectives and singulatives (e.g., kelynn ‘holly (collective)’, kelennenn ‘a holly tree’ with singulative suffix).

Prepositions and inflected forms

Prepositions inflect to incorporate pronominal objects (a hallmark of Celtic):

-

gans ‘with’: genev ‘with me’, genes ‘with you (sg.)’, ganso ‘with him’, ganthi ‘with her’, gansyn ‘with us’, gansowgh ‘with you (pl.)’, gansans ‘with them’.

-

dh’ / dhe ‘to’: _dhymm_ ‘to me’, _dhyb_ ‘to you (sg.)’, _dhedho**_ ‘to him’, etc.

Examples:

-

Genev vy yw an lyver. ‘I have the book (lit. the book is with me).’

-

Dhywhy a skrifav. ‘I’ll write to you (pl.).’

Similarities and differences with Welsh and Breton

Cornish, Welsh, and Breton form a dialect continuum historically, and many features align. Yet each language has innovated separately in phonology, lexicon, and standardisation.

Quick lexical snapshots

-

‘water’: Cornish dowr / dour, Welsh dŵr, Breton dour

-

‘sun’: Cornish howl, Welsh haul, Breton heol

-

‘head’: Cornish penn, Welsh pen, Breton penn

-

‘day’: Cornish dedh, Welsh dydd, Breton deiz

-

‘child’: Cornish flogh, Welsh plentyn, Breton bugel

-

‘house’: Cornish chy/chi, Welsh tŷ, Breton ti

Comparative table: grammar and lexis

| Feature | Cornish (Kernewek) | Welsh (Cymraeg) | Breton (Brezhoneg) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language family | Brythonic (Insular Celtic) | Brythonic | Brythonic | All close relatives |

| Definite article | an | y/yr/’r | an/ar/al | All have a single definite article |

| Indefinite article | None (use unn ‘one’ if needed) | None (use un ‘one’) | None (use ur ‘a/one’) | Breton ur functions as an article-like element |

| Demonstratives | Post-posed: an N ma/na | Post-posed: y N yma/yna | Post-posed: an N-mañ/-se/-hont | Structure is parallel; forms differ |

| Typical clause order | VSO in many main clauses | VSO in many main clauses | VSO in many main clauses | Verb-initial hallmark, with flexibility |

| Initial mutations | Soft, aspirate/mixed (revived norms vary) | Soft, nasal, aspirate | Soft (lenition), hardening, spirant, mixed | Systems differ in labels and triggers |

| Progressive | bos + ow + VN | bod + yn + VN | bezañ + o + VN | The ‘o/ow/yn’ progressive preposition is cognate |

| Possessive ‘my’ | ow (triggers soft mutation) | fy/fy (often causing mutation) | ma (mutation triggers) | All trigger mutation |

| Inflected prepositions | Yes (e.g., genev) | Yes (e.g., gennyf) | Yes (e.g., ganin) | Direct cognates |

| ‘water’ | dowr/dour | dŵr | dour | Near-identical across three |

| ‘sun’ | howl | haul | heol | Systematic sound correspondences |

| Standardisation | SWF (2008) in public use | Standard Welsh (BSL/WJEC norms) | Peurunvan (KU), Skolveurieg (KLT), etc. | Each has modern standards |

Example sentences (with glosses)

-

Definite vs. none

-

An venyn a wra kana.

the woman PRT does sing

→ ‘The woman sings.’ -

Benyn a wra kana.

woman PRT does sing

→ ‘A woman sings.’

-

Demonstratives

-

An chi ma yw bras. → ‘This house is big.’

-

An lyver na yw coth. → ‘That book is old.’

-

VSO and mutation with particles

-

A wel vy an den. → ‘I see the man.’

-

Ny welav vy an den. → ‘I do not see the man.’

-

Progressive with verbal noun

-

Yth eson ni ow studhya Kernowek. → ‘We are studying Cornish.’

-

Prepositions inflected

-

Genev vy yw an tus. → ‘The people are with me.’

-

Dhyworthyn y dhywgh gans lowena. → ‘From us to you with joy.’

-

Future/present stem

-

Gwerthav vy bara de Maine. → ‘I will sell bread tomorrow.’

-

Gwerthav vy bara pub dedh. → ‘I sell bread every day.’

(Orthographic details vary by tradition; the examples above broadly reflect the Standard Written Form with some widely understood variant shapes.)

Phonology (very brief)

Cornish contrasts a set of plosives, fricatives, nasals, liquids, and glides, with stress typically on the penultimate syllable in polysyllables (though historical layers and loanwords can differ). Vowel quality and quantity vary by dialectal reconstruction (Middle vs. Late Cornish bases), and the revived language has a regularised phoneme inventory for teaching.

Writing systems and orthography

Because revivalists drew on manuscripts from multiple stages, several spelling systems emerged in the twentieth century. The SWF attempts to balance historical evidence with learnability and cross-community acceptance. It provides consistent rules for mutation marking, vowel quality, and the treatment of etymological vs. phonemic spellings, enabling use in schools and public authorities. Learners will also encounter Kernewek Kemmyn, Unified Cornish, Unified Cornish Revised, and Late/Modern Cornish spellings in older textbooks and literature.

Sociolinguistic notes

Cornish is used in bilingual signage across Cornwall, in nursery and primary school activities, and in adult education through community classes. There are place-name standardisation projects, Cornish-language music, online content, and regular cultural events. While overall speaker numbers remain modest, intergenerational transmission exists in some families, and the language functions as a focal point for cultural identity within Cornwall.

Learning pointers (grammar-first)

-

Master mutations early (soft mutation patterns; common triggers like an, ow, possessives, and particles).

-

Use bos ‘to be’ confidently for progressives (yth esov vy ow…) and equatives (yth yw hemma…).

-

Get comfortable with VSO order in main clauses and how particles (affirmative a, negative ny/na) reshape the clause.

-

Build phrases with inflected prepositions (genev, dhywhy, ganso, etc.).

-

Read across Welsh and Breton examples; cognates and structures often map one-to-one.

Conclusion

Cornish is a Brythonic Celtic language whose structure reflects deep kinship with Welsh and Breton while showcasing its own historical trajectory. Despite dormancy as a community vernacular by the late eighteenth century, the twentieth-century revival has produced a living—if small—speech community with standardised orthography, education, and public presence. Grammatically, Cornish epitomises core Brythonic features: the absence of an indefinite article, a single definite article an, post-posed demonstratives, robust initial mutations, VSO-leaning clause patterns, and widespread periphrasis with verbal nouns. Its story—of continuity, change, loss, and revival—makes Cornish both an object of scholarly interest and a vibrant part of contemporary Cornish culture.