The Celtic language family

The term Celtic languages refers to a group of languages that constitute one branch of the large Indo‑European language family (IE) tree. In brief: the Celtic languages descend from a reconstructed ancestor known as Proto‑Celtic (also called Common Celtic), which in turn had emerged from the broader Indo-European linguistic stock.

As part of the Indo-European family, the Celtic branch sits alongside other major branches such as Italic (including Latin and the Romance languages), Germanic, Hellenic (Greek), Balto-Slavic, Indo-Iranian and others.

The Celtic languages are often discussed in terms of their internal classification, their origins and spread, their later decline on the European continent, and their survival (in much reduced form) in the British Isles and Brittany. This article will outline the origins and development of the family, its principal branches, how they emerged and developed, and then compare in broad strokes the Celtic group with the Latin/Italic (Romance) languages by means of a lexical and grammatical table of similarities and differences.

Origins and early history

The ancestor of the Celtic languages, Proto-Celtic, is a reconstructed language hypothesised to have been spoken perhaps between roughly 1300 BC and 800 BC (with some variation in the estimates) in Central or Western Europe. The precise homeland (Urheimat) of the Proto-Celts is debated, but many scholars associate the Hallstatt culture (late Bronze Age / early Iron Age Europe) as part of the cultural/linguistic horizon of early Celtic.

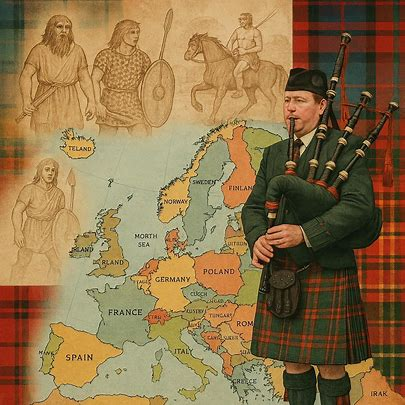

From this Proto-Celtic base, the Celtic-speaking peoples spread across large swathes of Europe: from Iberia (the Iberian Peninsula) to Gaul (modern France and beyond), even into Anatolia (Galatia) and north into Britain and Ireland.

For example, the scholars note that Celtic languages in Roman and pre-Roman times were spoken widely in Western Europe.

Among striking features of early Celtic is the loss of the Indo-European p-sound in initial position (an inherited *p from PIE becomes lost or transformed) in Proto-Celtic. The small inscriptions of Lepontic (in the Alps) from around the 6th century BC are among the earliest written attestations of a Celtic language.

Classification: branches and sub-branches

The classification of Celtic languages is somewhat complex and there is not full consensus on every detail, but the standard broad distinction is between Continental Celtic and Insular Celtic.

-

Continental Celtic refers to those Celtic languages once spoken on the European mainland (and even Anatolia) which are now extinct. This includes languages such as: Gaulish (in ancient Gaul), Celtiberian (in Iberia), Lepontic (northern Italy/Alps) and others (Gallaecian, Noric).

-

Insular Celtic refers to those Celtic languages of the British Isles and Brittany (the latter being continental but derived from migrants from Britain).

Within Insular Celtic one commonly distinguishes two sub-groups:

-

The Goidelic (or Gaelic) group, comprising Irish (Gaeilge), Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), and Manx (Gaelg).

-

The Brythonic (sometimes spelled Brittonic) group, comprising Welsh (Cymraeg), Cornish (Kernowek), and Breton (Brezhoneg).

Another classification criterion sometimes used is the so-called “P-/Q-Celtic” distinction: broadly speaking, languages which reflect Proto-Celtic *kʷ initial as a “p” sound (P-Celtic) versus those which reflect it as “k” or “c” (Q-Celtic). According to this system, Brythonic languages are P-Celtic, and Goidelic are Q-Celtic. Celtic Iberian may fall into Q-Celtic.

Over time, as the Celtic languages evolved, the Continental Celtic languages died out, largely under Roman and later Germanic and Romance language pressure, while the Insular languages continued (though many also experienced decline).

Development and historical trajectories

Continental Celtic

On the continent, Celtic languages were widely spoken in the Iron Age. For example, Gaulish inscriptions are found, and various tribal names recorded by Greek and Roman authors reflect Celtic languages. With the expansion of the Roman Empire and the spread of Latin (and later the Romance languages) plus Germanic incursions, the Continental Celtic languages gradually ceased to exist as living vernaculars. Their decline was a long process of language shift. The inscriptional and epigraphic record of Continental Celtic is fragmentary, so our knowledge of their development is limited.

Insular Celtic

In the British Isles and Brittany, Celtic languages survived far longer. In Ireland, for instance, Old Irish texts begin to appear in the 6th-7th century AD (in ogham script, later Latin script). Welsh has a continuous record of written literature from around the 6th-7th century onward as well. Cornish and Manx suffered language decline (Cornish effectively extinct as community language by the 18th–19th century, Manx by the 20th century) but both have been revived.

In terms of linguistic innovations, the Insular Celtic languages developed distinctive features: for example, inflected prepositions (prepositions fused with pronouns), VSO (verb-subject-object) word order (in many cases), and initial consonant mutations (especially in Brythonic languages) are typical of the Insular branch.

Within the sub-branches, for example, the Goidelic languages evolved from Primitive Irish → Old Irish → Middle Irish → Early Modern Irish → Modern Irish (and parallel developments for Scottish Gaelic and Manx). The Brythonic side evolved from Common Brittonic (the Celtic language of Iron-Age Britain) into Old Welsh, Cornish, and Breton (after migration to Brittany).

Language revival efforts in the modern era (e.g., Welsh, Irish, Cornish, Manx) have meant that the Celtic languages remain extant (though all are minority languages and many are endangered).–

Key linguistic features and distinctions

Celtic languages share many inherited Indo-European traits (through Proto-Celtic) but also exhibit features that distinguish them from many other IE branches. Some of these include the loss of *p in Proto-Celtic, the development of consonant mutations (in Insular Celtic), prepositional pronouns, VSO syntax, and others.

Meanwhile, the Latin/Italic branch (and hence the Romance languages descended from Latin) follow a different path: Latin is the ancestor of the Romance or Italic languages, which preserved a large part of the morphological case-system, and then developed into analytic forms in many modern Romance languages.

Below is a comparative table summarising lexical and grammatical similarities and differences between Celtic (represented in broad terms) and Latin/Italic (again broadly).

In summary: while Celtic and Latin both belong to the Indo-European family and hence share a distant ancestry, their paths diverged long ago. Latin (and the Italic branch) ultimately gave rise to the Romance languages; Celtic, in contrast, developed its own distinct branches, many of which have died out, leaving only a handful of living languages and communities today. The features of Celtic languages—such as initial sound loss, mutation phenomena, VSO order and inflected prepositions—mark them out as a distinctive branch, with structural differences from the Latin/Romance lineage.

Similarities and differences: commentary

It is worth noting that some scholars have argued for an earlier “Italo-Celtic” grouping (i.e., a common ancestor for Italic and Celtic) on the basis of certain shared innovations (for example particular verbal morphology) though this remains debated. In practice, the degree of similarity between Celtic and Latin/Italic is lower than that between Latin and its Romance descendants.

From the lexical side, the major reason one sometimes sees lexical similarities is either that both Celtic and Latin inherited vocabulary from Proto-Indo-European (so the similarity is because of shared ancestry), or that Latin (and later Romance) passed loanwords into Celtic (especially in contact zones). It is less commonly the case that Celtic and Latin share unique inherited innovations not found elsewhere.

One illustrative example: in the P-/Q-Celtic distinction table, the Proto-Celtic *kʷenkʷe (‘five’) appears as *pumpe in P-Celtic languages, but as *cúig / *coíig in Goidelic (Q-Celtic) and Latin has quinque. The shared root is visible, but the divergence is clear.

In grammatical structure, the presence of initial mutations, inflected prepositions and verb-initial order in Insular Celtic are markedly different from Latin’s more typical SOV/SVO order, lack of mutation phenomena, and more freely ordered classical syntax. The morphology of Latin remained relatively conservative (for an IE language) for longer, whilst Celtic underwent changes such as the loss of *p and the development of different syntactic structures.

Thus, while one can identify broad familial relationships and some common traits (shared PIE roots, similar morphological typology originally), the Celtic family is sufficiently divergent from Latin/Italic such that one cannot treat Celtic as a “sister” in the sense of being immediately comparable to Romance-Latin; rather, they are fellow branches of the large IE tree.

Concluding remarks

The Celtic language family is rich in history and significance. From its Proto-Celtic roots in the early Iron Age of Europe, through the widespread Celtic-speaking communities of the continent and their decline, to the survival (and revival) of languages in the British Isles and Brittany, the story of Celtic languages is one of change, resilience and adaptation. Its internal divisions—Continental versus Insular, Goidelic versus Brythonic (or P- versus Q-Celtic)—reflect both geography and sound-change history.

In comparison to the Latin/Italic branch, the Celtic languages share a distant common ancestry (as Indo-European) but have followed a different evolutionary path, both phonologically and grammatically. The Latin-Romance lineage is more straightforward in descent, whereas the Celtic lineage is more fragmentary (with many extinct branches) and features some typologically unusual traits (at least within Europe) such as initial consonant mutation and verb-initial word order.

For those interested in historical linguistics, the Celtic languages offer a fascinating insight into how a language family can diverge, survive (in limited form), and interact with dominant neighbouring languages (Latin, English, French, etc.). Their study helps enrich our understanding of the broader Indo-European family, of language contact and decline, and of the rich tapestry of Europe’s linguistic past.