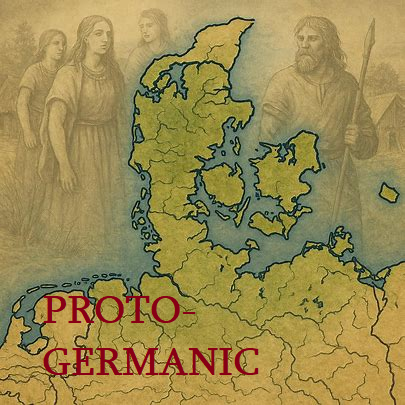

Proto-Germanic: The Ancestral Language of English, German, and the Norse Tongues

Proto-Germanic is the reconstructed ancestor of all Germanic languages, including English, German, and the Scandinavian tongues. Spoken in Northern Europe during the first millennium BCE, it evolved from Proto-Indo-European and underwent distinct sound changes, notably Grimm’s Law and Verner’s Law, shaping the linguistic foundation of the Germanic family.

Introduction

Proto-Germanic is the reconstructed ancestor of all Germanic languages—the linguistic forebear of English, German, Dutch, and the Scandinavian tongues. Though no written records of Proto-Germanic exist, linguists have reconstructed much of its phonology, grammar, and vocabulary through the comparative study of its descendant languages and related Indo-European branches. It represents the transitional stage between Proto-Indo-European and the earliest attested Germanic languages, such as Gothic, Old Norse, and Old English.

The study of Proto-Germanic provides invaluable insights into the origins of the modern Germanic languages, their internal relationships, and the phonological laws that define them. It also illustrates the processes by which Indo-European dialects diversified across prehistoric Europe.

(Read more about The Germanic Language Family here)

Origins within the Indo-European Family

Proto-Germanic descended from Proto-Indo-European (PIE), the hypothesized ancestor of most European and many Asian languages. The Germanic branch likely began diverging from its Indo-European parent during the late second millennium BCE. This linguistic split is marked by a series of systematic phonological and morphological innovations, many of which distinguish the Germanic family from all other Indo-European groups.

Among these innovations were the consonantal shifts formalized in Grimm’s Law, the simplification of the PIE tense-aspect system into a binary tense contrast (present and past), and the introduction of strong and weak verb classes. The result was a coherent but distinct proto-language spoken by early Germanic peoples in Northern Europe.

The Chronology and Geographic Range of Proto-Germanic

Most scholars place Proto-Germanic between roughly 500 BCE and 200 CE, a period that saw increasing contact between Germanic speakers and Celts, Balts, and early Romans. Its geographic heartland likely stretched from the southern Baltic coast through Jutland and northern Germany.

Over time, dialectal variation developed within Proto-Germanic communities. These dialects would later crystallize into the three traditional branches of the family: North Germanic, West Germanic, and East Germanic.

(Internal links: The North Germanic Family, The West Germanic Family, The East Germanic Family)

Grimm’s Law: The First Germanic Sound Shift

One of the most distinctive features of Proto-Germanic phonology is the set of consonant changes known as Grimm’s Law, first formulated by Jacob Grimm in the nineteenth century. This law describes how Proto-Indo-European voiceless, voiced, and aspirated stops shifted systematically into new sounds in Proto-Germanic.

| PIE | Proto-Germanic | Example (PIE → PGmc → English) |

|---|---|---|

| p, t, k | f, þ, h | pód- → fōt → foot |

| b, d, g | p, t, k | déḱm̥ → tehun → ten |

| bh, dh, gh | b, d, g | bher- → beran → bear |

This systematic shift produced the characteristic “hardness” of the Germanic consonant system and marks one of the earliest identifiable stages in the formation of Proto-Germanic.

Verner’s Law: Refining the Pattern

Karl Verner’s discovery in 1875 explained apparent irregularities in Grimm’s Law. He found that Proto-Germanic voicing patterns were influenced by the placement of stress in the Proto-Indo-European ancestor. When the stress followed the consonant in PIE, the resulting Proto-Germanic sound became voiced.

For instance:

-

PIE pátēr → Proto-Germanic fadar (stress on first syllable, no voicing)

-

PIE bhrā́ter → Proto-Germanic brother (stress on second syllable, voicing applied)

Together, Grimm’s Law and Verner’s Law illustrate the systematic, rule-governed nature of sound change and have served as models for modern historical linguistics.

Phonology of Proto-Germanic

Proto-Germanic preserved many features of its Indo-European ancestor but reorganized its phonemic inventory. It had approximately 15 consonant phonemes and 9 vowels, including several diphthongs.

Consonant System (simplified):

p, b, t, d, k, g, f, þ, h, s, z, m, n, l, r, j, w

Vowel System:

a, e, i, o, u (short)

ā, ē, ī, ō, ū (long)

plus diphthongs ai, au, eu, iu

Stress in Proto-Germanic was fixed on the first syllable of the root, a major innovation that influenced subsequent phonological reductions and the erosion of many unstressed endings in later Germanic languages.

Morphology and Grammar

Proto-Germanic maintained a richly inflected morphological system, inherited from Proto-Indo-European but simplified in certain respects.

Nouns and Adjectives

Nouns were inflected for case (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative), number (singular, plural, and occasionally dual), and gender (masculine, feminine, neuter).

Adjectives agreed with their nouns in all these categories and developed both strong and weak declensions—a distinction preserved in Old English and Old High German.

Verbs

Proto-Germanic verbs were organized into strong and weak classes.

-

Strong verbs formed their past tense by ablaut, or vowel gradation (e.g., singan–sang–sungun–sunganaz, ‘to sing’).

-

Weak verbs formed their past tense using a dental suffix (-d- or -t-), as in fulljan–fullida (‘to fill’).

This strong/weak distinction, first visible in Proto-Germanic, became a hallmark of all later Germanic languages.

Pronouns

Personal pronouns retained the Indo-European categories but with simplified forms:

ik (I), þu (you), we (we), iz (he), si (she).

Syntax

Word order was relatively free, though the verb-second (V2) tendency—a feature of modern Germanic syntax—was likely already emerging.

Lexicon and Word Formation

The vocabulary of Proto-Germanic reflects both its Indo-European heritage and early innovations. Many basic terms are direct cognates across the modern Germanic languages.

| Proto-Germanic | Proto-Indo-European Root | English | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| fadar | pətér | father | male parent |

| broþar | bhrāter | brother | sibling |

| hundaz | kwōn | hound | dog |

| dæg | dyeu- | day | daylight |

| wōdaz | wēt- | wode / wit | mind, fury |

| sunþaz | sówel | sun | sun |

| steranō | ster- | star | star |

| watar | wodr | water | water |

This lexicon demonstrates how Proto-Germanic both preserved ancient Indo-European roots and developed new derivational patterns that would shape its descendant languages.

Transition to the Daughter Languages

By the early centuries CE, Proto-Germanic had diversified into distinct dialect zones. Geographic separation, migration, and contact with neighboring peoples accelerated differentiation.

Three major groups emerged:

-

North Germanic, leading to Old Norse and the modern Scandinavian languages.

-

West Germanic, the ancestor of Old English, Old High German, and Old Dutch.

-

East Germanic, represented by Gothic and other now-extinct languages.

Although mutual intelligibility probably persisted for some time, by the 4th century CE the Proto-Germanic continuum had effectively fragmented into separate languages.

Key Comparative Features

| Feature | Proto-Germanic | West Germanic | North Germanic | East Germanic |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Writing system | None (spoken only) | Runic → Latin | Runic → Latin | Gothic alphabet |

| Stress | Fixed on first syllable | Fixed | Fixed | Fixed |

| Past tense formation | Strong/weak verbs | Preserved | Preserved | Preserved |

| Noun cases | 4 | 4–5 | 4–6 | 4 |

| Dual number | Present | Lost early | Retained longer | Retained |

Influence on Modern Germanic Languages

Proto-Germanic remains the foundation upon which all later Germanic languages are built. Its phonological and grammatical systems continue to shape English, German, Dutch, and the Scandinavian languages. For example, the ablaut patterns of English sing–sang–sung and the dental suffix of walked reflect directly Proto-Germanic formations.

Furthermore, Proto-Germanic introduced numerous semantic and morphological innovations that distinguished its descendants from other Indo-European families. Its stress patterns and vowel reductions influenced the analytic tendencies that characterize English, while its morphological conservatism persists in the inflected systems of Icelandic and German.

The Role of Reconstruction

Because Proto-Germanic was never written, its features are inferred through the comparative method. Linguists analyze systematic correspondences among attested Germanic languages and trace them back to a common source. This method allows for the reconstruction of sound systems, morphological paradigms, and even vocabulary with remarkable precision.

Reconstructed forms are conventionally preceded by an asterisk (*) in scholarly notation, indicating that they are not directly attested but inferred. In this article, forms are presented in simplified orthography for clarity.

Conclusion

Proto-Germanic occupies a central position in the study of Indo-European linguistics. It represents a stage of linguistic evolution that links prehistorical Indo-European speech with the historically attested Germanic languages of the early Middle Ages. Through systematic sound changes—particularly Grimm’s and Verner’s Laws—and a well-defined morphological system, it established the framework for the later development of English, German, Dutch, and the Scandinavian tongues.

Although no documents survive from its time, Proto-Germanic endures as a rigorously reconstructed linguistic system, a testament to the precision of the comparative method and the deep interconnectedness of the world’s languages.

(Internal links: The Germanic Language Family, The West Germanic Family, The North Germanic Family, The East Germanic Family)