The Manx Language and its Linguistic Context

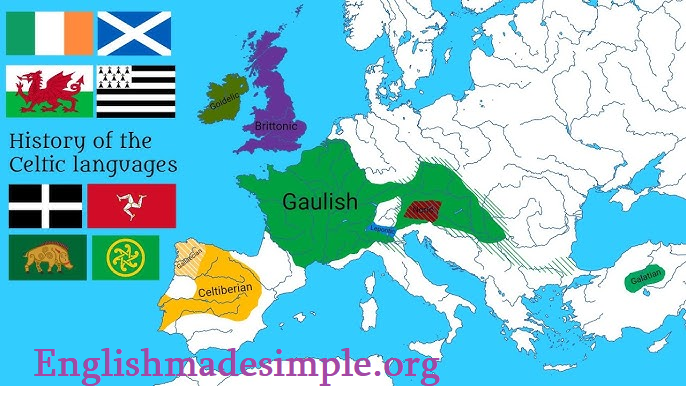

The Manx language (Manx: Gaelg or Gailck) is a member of the Goidelic branch of the Celtic language family, which itself forms part of the large Indo-European language family. Although sometimes referred to as an individual language rather than a family, Manx exists within a clear genealogical network of related languages. Its closest linguistic relatives are Irish (Gaeilge) and Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), with which it forms the Goidelic subgroup. Manx, therefore, is not an isolated language but a unique expression of a shared Gaelic linguistic tradition.

Language Family Diagram

Origins and Historical Development

The origins of Manx can be traced back to Primitive Irish, spoken in Ireland during the first millennium BCE. By the 4th to 6th centuries CE, this had evolved into Old Irish, the common ancestor of Manx, Irish, and Scottish Gaelic. The Isle of Man, located in the Irish Sea, saw significant cultural interchange with both Ireland and Scotland, leading to the adoption of a Gaelic language early in the medieval period.

Before Gaelic became dominant, it is believed that the island’s population spoke a Brythonic Celtic language, related to early Welsh. Over time, Gaelic replaced this, possibly through migration and settlement from Ireland.

Norse Influence

The Viking presence from the 9th century introduced Norse rule and settlement. This influence is still visible in:

-

Place-names (Laxey, Ramsey, Langness)

-

Maritime vocabulary (e.g., skell “roost”, trawler terms)

-

Political terms such as Tynwald, the island’s parliament (from Old Norse þingvǫllr, “assembly field”).

However, the core grammar and syntax remained Goidelic, with Norse influence confined mostly to vocabulary.

Separation and Divergence

By the 13th century, Manx had begun to diverge from the Gaelic spoken on either side of the Irish Sea. The Isle of Man passed under various rulers—Scottish, Norse, and English—each contributing to shifts in literacy, cultural orientation, and language standardisation.

Manx differs from Irish and Scottish Gaelic primarily due to:

-

Distinctive pronunciation shaped by insular development

-

Orthography influenced by English spelling rather than classical Gaelic spelling conventions

Decline and Revival

By the 19th century, English had displaced Manx as the dominant language in education and public life. The last traditional native speaker, Ned Maddrell, died in 1974. However, before the language ceased to be spoken natively, researchers recorded conversations and collected extensive documentation, which proved essential for revival efforts.

Today:

-

Manx is taught in schools.

-

There are fluent second-language speakers.

-

Public signage increasingly appears in bilingual form.

-

Manx media, radio broadcasting, and community cultural activities support use.

The language is now recognised as a revitalised community language, not extinct.

Manx Grammar

Manx grammar shares many characteristics with Irish and Scottish Gaelic but has its own distinctive forms, especially in pronunciation and spelling.

1. Articles (Definite and Indefinite)

Manx does not have an indefinite article. Therefore:

-

dooinney = “a man” / “man” (general)

-

ben = “a woman” / “woman” (general)

The definite article is:

| Number | Article | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Singular | yn | yn dooinney – the man |

| Plural | ny | ny deiney – the men |

Example sentences:

-

Ta dooinney ayn. – There is a man.

-

Ta yn dooinney ayn. – The man is here.

-

Va ny deiney er y traie. – The men were on the beach.

2. Demonstrative Pronouns

Demonstratives are placed after the noun:

| Meaning | Form | Example |

|---|---|---|

| this | shoh | yn ben shoh – this woman |

| that | shen | yn ben shen – that woman |

Example sentences:

-

Ta mee gra rish yn dooinney shoh. – I am speaking to this man.

-

Cha nione dou yn thie shen. – I do not know that house.

3. Word Order (VSO)

As in the other Goidelic languages, the standard Manx word order is Verb–Subject–Object.

-

Ta mee goll. – Am-going I (I am going).

-

Va eh jannoo e obbyr. – Was he doing his work (He was doing his work).

However, revival speech sometimes shifts toward SVO under English influence.

Examples:

| Standard (VSO) | English |

|---|---|

| Ta Adryn gobbal ny moddee. | Adrian is feeding the dogs. |

| Cha row mee dy mie jiu. | I was not well today. |

4. Verbs and Tenses

The verb to be is central and frequently used with verbal nouns (similar to English -ing forms).

| Tense | Verb Form | Example | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | ta | Ta mee ayn. | I am here. |

| Past | va | Va mee ayn. | I was here. |

| Future | bee | Bee mee ayn. | I will be here. |

| Negative Present | cha nel | Cha nel mee ayn. | I am not here. |

| Negative Past | cha row | Cha row mee ayn. | I was not here. |

Example sentences:

-

Ta mee goll dys yn ard. – I am going to the high place.

-

Bee oo erash mairagh? – Will you be back tomorrow?

5. Initial Consonant Mutation

Manx uses lenition, changing initial sounds based on grammatical context.

| Base Form | Lenited Form | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ben (woman) | ven | yn ven – the woman |

| kione (head) | chione | my chione – my head |

Comparison with Irish and Scottish Gaelic

While all Goidelic languages share a common grammatical and lexical base, they differ in pronunciation, idiom, and spelling.

Comparison Table

| Feature | Manx (Gaelg) | Irish (Gaeilge) | Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word for language | Gaelg | Gaeilge | Gàidhlig | Cognates |

| Definite article (sg.) | yn | an | am/an | Manx form influenced by English spelling |

| Plural article | ny | na | na | Similar to Gaelic |

| “I am” | Ta mee | Tá mé | Tha mi | Nearly identical structure |

| “This” | shoh | seo | seo | Manx uses sh where others use s |

| Word order | VSO | VSO | VSO | Shared Goidelic structure |

| Orthographic style | English-based | Gaelic-based | Gaelic-based | Major visible difference |

Conclusion

The Manx language represents a unique and culturally rich expression of the Goidelic Celtic heritage. While clearly related to Irish and Scottish Gaelic, Manx developed independently, shaped by the Isle of Man’s geography, history, and shifting cultural influences. Its distinctive grammar, sound system, and spelling conventions reflect centuries of adaptation and continuity.

The remarkable revival of Manx in the late 20th and early 21st centuries stands as a powerful example of cultural resilience. Today, Manx lives not only in classrooms, signage, and broadcast media but in daily speech among islanders committed to ensuring that their ancestral language continues to thrive.

Manx is not a relic; it is a living language.