Goidelic Languages

The Goidelic (or Gaelic) languages form one of the two principal branches of the Insular Celtic subgroup within the Celtic branch of the Indo-European family. Their sister branch is Brittonic (Welsh, Cornish, Breton). Goidelic comprises Irish (Gaeilge), Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), and Manx (Gaelg/Gailck). The name “Goidelic” derives from Goídel, a medieval form referring to Gaelic speakers and their language.

This article outlines the Goidelic languages’ classification and relatives, traces their origins and historical development, explains how their modern sub-branches emerged, and compares their structure and lexicon—both internally and against the other Insular Celtic languages. Two simple diagrams (a family tree and a historical timeline) are provided, along with comparative tables.

Classification and Related Families

Indo-European → Celtic → Insular Celtic → Goidelic (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx)

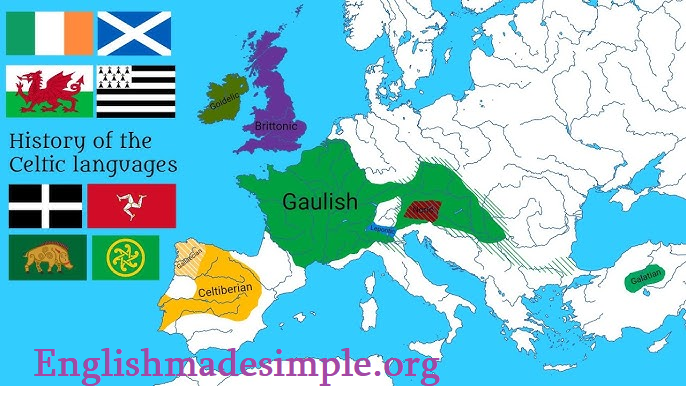

Within Indo-European, Celtic is commonly divided into Insular Celtic (Goidelic + Brittonic) and Continental Celtic (now extinct: Gaulish, Celtiberian, Lepontic, etc.). Goidelic and Brittonic share innovations that set them apart from Continental Celtic (e.g., core aspects of verbal syntax, periphrastic constructions, and initial consonant mutation as a grammaticised system), yet they also differ systematically: Goidelic is traditionally classed as Q-Celtic (retention of Proto-Celtic kw as /k/ or /c/), while Brittonic is P-Celtic (Proto-Celtic *kw > *p). Goidelic’s closest living relatives are therefore the Brittonic languages, but its wider kinship includes all Celtic (living and extinct), and ultimately all Indo-European languages.

Diagram 1: Family Tree

Origins: From Proto-Celtic to Primitive Irish

The Goidelic languages descend from Proto-Celtic, spoken in the late Bronze and early Iron Ages. The Celtic languages reached the British Isles by the first millennium BCE. On linguistic grounds, Insular Celtic likely developed a suite of shared innovations after settlement, giving rise to a Primitive Irish stage on the Goidelic side. Primitive Irish is directly attested in Ogham inscriptions (c. 4th–6th centuries CE), mostly in Ireland and parts of western Britain. These short epitaph-like texts show early forms of names and grammatical endings and demonstrate an already distinct Goidelic identity.

Key traits at or shortly after this stage include:

-

Q-Celtic reflexes (Proto-Celtic *kw > c/k, e.g., *ekwos ‘horse’ > Old Irish ech, Modern Irish each, Scottish Gaelic each, Manx eeast in some senses varies; note: Manx cabbyl ‘horse’ is a Norse loan).

-

Initial consonant mutation already emergent (later fully grammaticalised).

-

Verbal complex with inflectional endings and relative/vernacular alternations that become prominent in Old Irish.

Old Irish (c. 600–900): A Classical Goidelic Stage

Old Irish is exceptionally well documented (glosses in Latin manuscripts, legal tracts, sagas, religious texts). It exhibits:

-

Rich inflectional morphology, with a developed case system (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative), verbal person/number endings, and consonant mutation triggered by syntactic context.

-

Default VSO clause order, though Old Irish permits pragmatically conditioned variation.

-

Prepositional pronouns (prepositions inflected for person/number: dom ‘to me’, duit ‘to you’, etc.).

-

Relative clauses and special relative verb forms.

-

Lenition and nasalisation (eclipsis) used grammatically.

Old Irish became a learned language of culture across medieval Ireland and Gaelic Scotland, fostering a shared manuscript culture and mutually intelligible high style among Goidelic elites.

Middle Irish (c. 900–1200): Levelling and Transition

In Middle Irish, some of the most complex Old Irish contrasts begin to level:

-

Simplification of certain verbal alternations and case endings.

-

Expansion of periphrastic constructions (e.g., clefting, progressive forms).

-

Continued lexical borrowing (from Norse, Latin, and later Anglo-Norman French).

Middle Irish is a bridge to the dialectal differentiation that produces recognisably distinct Early Modern Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and later Manx.

Emergence of the Modern Sub-branches

Irish (Gaeilge)

-

Early Modern Irish (c. 1200–1650) reflects standardising tendencies in bardic poetry and prose.

-

After the seventeenth century, regional dialects crystallise (Ulster, Connacht, Munster), and a substantial literature continues despite sociopolitical pressures.

-

Modern Irish developed a standard written form in the twentieth century alongside major revival efforts and a central role in Irish national identity.

Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig)

-

Diverges from Irish during the medieval period through sound changes, lexical and morphosyntactic developments, and the geographical separation of Gaelic Scotland.

-

Classical Gaelic (shared literary standard used in Ireland and Scotland up to c. 17th century) fades as Scottish Gaelic adopts orthographic norms closer to actual speech.

-

Modern Scottish Gaelic exhibits distinct phonology (notably palatalisation contrasts), vocabulary, and a growing contemporary literature and media presence.

Manx (Gaelg/Gailck)

-

Develops on the Isle of Man from medieval Gaelic, with notable contact influences from English and Norse.

-

Undergoes sharp decline in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (the last native traditional speaker died in 1974), followed by a remarkable revival: new speakers, education programmes, broadcasting, and public signage have re-established Manx as a living community language.

Structural Profile of Goidelic

Across Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Manx, many core features are shared:

-

Default VSO word order.

-

Initial consonant mutation (lenition; plus eclipsis in Irish).

-

Rich verb morphology, with periphrastic progressives (e.g., Irish tá mé ag scríobh; Gàidhlig tha mi a’ sgrìobhadh; Manx ta mee screeu).

-

Prepositional pronouns (Irish leis, liom; Gàidhlig le, leam; Manx lesh, lhiam).

-

Inflected prepositions and consonant quality contrasts (broad vs slender in Irish/Gaelic; palatal effects reflected orthographically).

-

No true indefinite article; a definite article used with complex allomorphy.

Differences include the extent and triggers of mutation (Irish distinguishes lenition and eclipsis; Scottish Gaelic primarily lenition), orthographic conventions (Irish spelling reform; Gaelic retains older conventions), and phonological outcomes (e.g., vowel length/quality, treatment of historical consonant clusters).

Goidelic vs Other Insular Celtic (i.e., vs Brittonic)

Goidelic and Brittonic share many Insular innovations (VSO order, mutation, prepositional pronouns), but differ systematically in lexicon and certain morphosyntactic developments. The most famous diagnostic is Q vs P:

-

*Proto-Celtic kw → c/k in Goidelic (ekwos > Old Irish ech ‘horse’, Modern Irish each, Gàidhlig each),

but → p in Brittonic (Welsh ep/eb historically, Modern Welsh epos is not a native item; modern Welsh word is ceffyl, from Latin; better for the diagnostic is head: Irish ceann vs Welsh pen).

To keep examples robust, the classic illustration uses head and son:

-

‘Head’: Irish ceann, Gàidhlig ceann, Manx kione vs Welsh pen, Cornish pen, Breton penn.

-

‘Son’: Irish mac, Gàidhlig mac, Manx mac vs Welsh mab, Cornish mab, Breton mab.

Table 1. Lexical & Grammatical Comparisons (Goidelic vs Brittonic)

| Feature | Goidelic (Irish / Scottish Gaelic / Manx) | Brittonic (Welsh / Cornish / Breton) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Historical *kw reflex (Q vs P) | c/k: ceann ‘head’, mac ‘son’ | p: pen/penn ‘head’, mab ‘son’ | Classic diagnostic contrast. |

| Default clause order | VSO | VSO | Shared Insular Celtic trait (with variation). |

| Initial mutation | Lenition (all); eclipsis (Irish) | Lenition & other mutations | Systems differ in triggers and inventory. |

| Prepositional pronouns | Yes: liom, leat, leis; leam, leat, leis; lhiam, lhiat, lesh | Yes: Welsh gyda fi, i mi (less inflection; also synthetic forms in Breton/Cornish) | All show fusion of adposition + pronoun. |

| Definite/indefinite articles | Definite only; no true indefinite | Definite article; no true indefinite | Parallel systems. |

| Case morphology (nouns) | Residual (strongest in Old Irish; modern Irish retains genitive; case reduced elsewhere) | Case largely absent in modern forms | Diachronic reduction in both branches. |

| Verbal morphology | Rich synthetic & periphrastic | Rich periphrastic; synthetic forms vary | Both use analytic strategies extensively. |

| Relative clauses | Special relativised verb forms in older stages; modern particles (a, a tha, t’eh) | Particles (a, y, a zo, etc.) | Different particles, shared strategy. |

| Lexicon | Many inherited Celtic items; loans from Norse/English/Scots | Many inherited items; strong Romance (Latin/French) and English influence | Contact profiles differ. |

(Examples are illustrative; each language has additional, language-specific details.)

Table 2. Comparison Within Goidelic

| Property | Irish (Gaeilge) | Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) | Manx (Gaelg/Gailck) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISO code | ga | gd | gv |

| Historical centre(s) | Ireland (all provinces; modern strongholds especially in the west) | Highlands & Islands (Hebrides, Skye; urban communities too) | Isle of Man |

| Standardisation | Official standard orthography; regional dialects (Ulster/Connacht/Munster) | Orthography reflects historical conventions; dialectal diversity (Hebridean, Skye/Lochalsh, etc.) | Orthography influenced by English phonetics; revived standard shaped by early grammarians and modern teaching |

| Mutation | Lenition and eclipsis | Primarily lenition (plus assorted sandhi) | Lenition-type alternations; system simplified relative to Irish |

| Verb ‘to be’ | Tá / Is (existential vs copular); rich periphrasis (tá mé ag…) | Tha / Is; periphrasis (tha mi a’…) | Ta / She/Shee; periphrasis (ta mee…) |

| Prepositional pronouns | liom, leat, leis… | leam, leat, leis… | lhiam, lhiat, lesh… |

| Plural formation | Mixed strategies; productive endings (-í/-íthe), suppletion | Mixed; many inherited plurals | Mixed; analogies and regularisations in revival era |

| Phonology (sketch) | Broad vs slender consonants; stress typically initial; vowel harmony effects in spelling | Strong palatalisation contrasts; complex vowel inventory; often word-initial stress | Strong reduction of unstressed syllables; distinctive outcomes of historical clusters |

| Status & vitality | Official language in Ireland; school system, media, literature, Gaeltacht areas | Recognised minority language in Scotland; schooling, media (BBC Alba), growing urban use | Revived community language; education (Bunscoill Ghaelgagh), broadcasting, public visibility |

| Notable contact | English (anglicisation), Norse (coastal), Scots in Ulster | Scots and English; Norse substratal influence in the north/west | Norse (lexicon), English; unique insular developments |

Sound Changes and Orthographies (high-level notes)

-

Irish implemented significant spelling reform in the twentieth century, moving towards a more phonologically transparent orthography (e.g., removing many silent letters).

-

Scottish Gaelic retains more historical spellings, often mapping to dialectal pronunciations through rules familiar to literate communities.

-

Manx orthography, historically codified through religious texts (e.g., the Manx Bible) and grammarians, is English-based in its letter-to-sound correspondences, making it immediately approachable to English readers but less obviously cognate at a glance (e.g., Irish mac ~ Manx mac, but Irish ceann ‘head’ ~ Manx kione).

Morphosyntax: Shared Patterns and Divergences

All Goidelic languages display VSO tendencies and make extensive use of periphrastic aspect, especially the progressive with a verbal noun. Initial mutations mark grammatical relationships (e.g., after certain particles or the definite article). Copular and existential verb distinctions are central (Irish is vs tá; Gaelic ’s e vs tha), shaping equational and presentational sentences.

Divergences include:

-

Mutation triggers and inventories (Irish uniquely has eclipsis widely in the standard system; Gaelic relies more on lenition and sandhi).

-

Relative and subordinate clauses (particle inventories and agreement patterns differ).

-

Case remnants (Irish preserves a productive genitive and set phrases; Gaelic shows fewer overt case distinctions; Manx is largely analytic).

Contact, Borrowing, and Revival

The Goidelic languages have long been in contact with Germanic neighbours:

-

Norse left loanwords (maritime, trade, household domains) and arguably substratal influences.

-

English/Scots contributed vocabulary, calques, and code-switching dynamics. The degree and nature of borrowing vary regionally and historically.

Revival and maintenance efforts have reshaped the sociolinguistic landscape:

-

Irish enjoys state support, education through Irish, and significant media presence.

-

Scottish Gaelic benefits from statutory recognition, schooling, digital content, and a strong cultural profile in the Highlands and Islands.

-

Manx, once moribund, is a success story of revitalisation, with new generations of speakers and a visible public domain.

The Bigger Insular Picture

Set against Brittonic, Goidelic shares the Insular Celtic signature (VSO, mutation, prepositional pronouns, periphrastic tense/aspect) yet diverges in:

-

Historical sound change (Q vs P), producing widespread lexical correspondences: ceann vs pen, mac vs mab, etc.

-

Specific morphosyntactic realisations (Irish eclipsis; Welsh’s more elaborate mutation series including nasal and aspirate mutations with different triggers).

-

Lexical outcomes under contact (Brittonic shows strong Romance influence via long Latin contact; Goidelic’s Germanic contact has different timelines and domains).

Concluding Remarks

The Goidelic languages exemplify both deep historical continuity (from Ogham-inscribed Primitive Irish through Old Irish’s classical literature) and adaptive modern vitality (revival, education, digital media). Their internal diversity—Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx—is substantial yet rooted in a shared structural core that is unmistakably Goidelic and recognisably Insular Celtic.

From the early Proto-Celtic dispersals to the Insular innovations that shaped their grammar, from the medieval high culture of Old and Middle Irish to the modern revitalisations, the Goidelic languages offer a panoramic view of how a language family can change, differentiate, and endure. Their comparative study—internally and against their Brittonic cousins—continues to illuminate the pathways of sound change, grammar formation, and the social forces that sustain (or imperil) linguistic communities.