Brythonic (Brittonic) Celtic languages

Overview

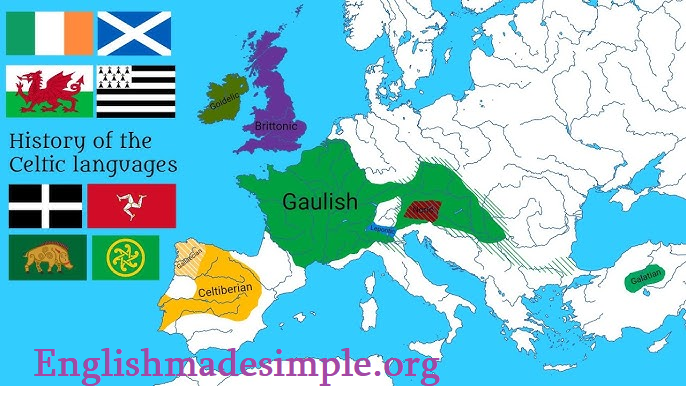

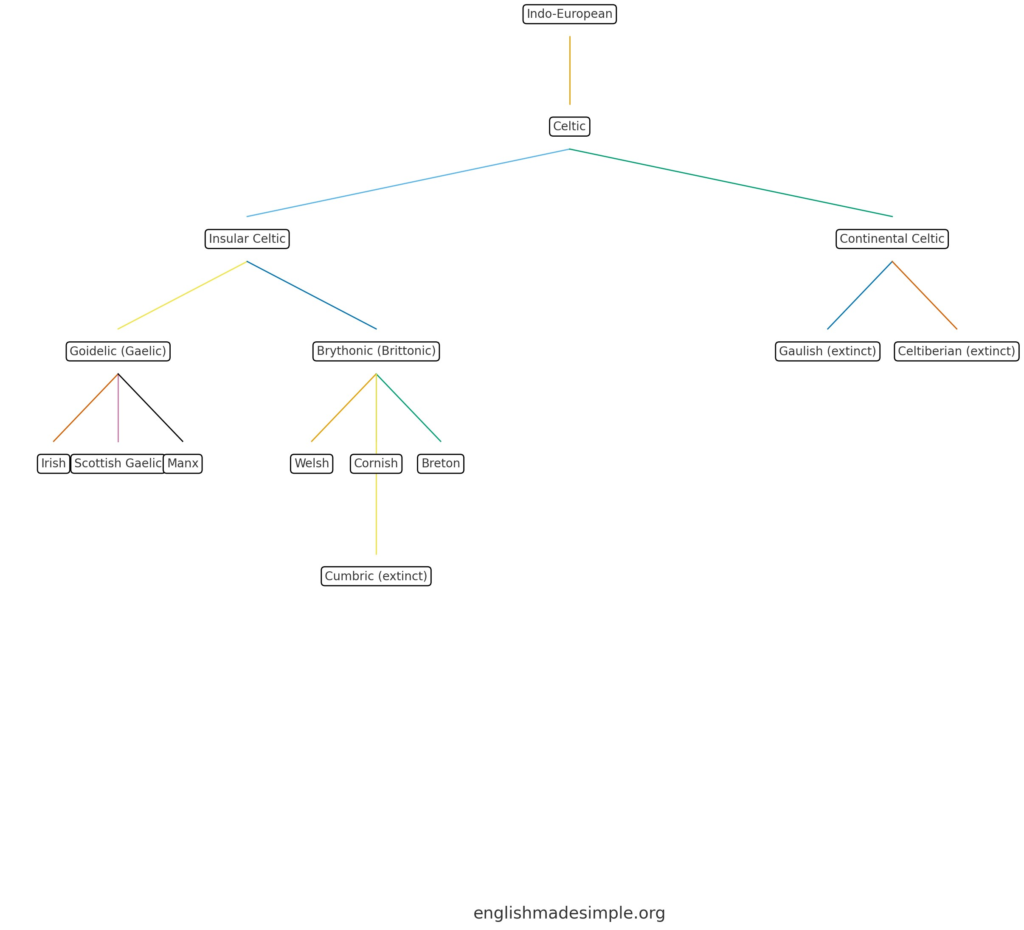

The Brythonic (often spelled Brittonic) Celtic languages form one of the two main sub-branches of the Insular Celtic group, the other being the Goidelic (Gaelic) branch.

They belong to the broader Celtic branch of the Indo-European language family.

In modern times the principal living Brythonic languages are Welsh (Cymraeg), Cornish (Kernowek) and Breton (Brezhoneg), with a number of extinct or revived languages/varieties such as Cumbric (extinct) also belonging to the group.

In what follows we trace the origins, history and development of the Brythonic branch, outline its subdivisions, and compare its features within the Insular Celtic family (Goidelic vs Brythonic) via a lexical/grammatical table and a further table comparing the individual Brythonic languages.

Origins and Early History

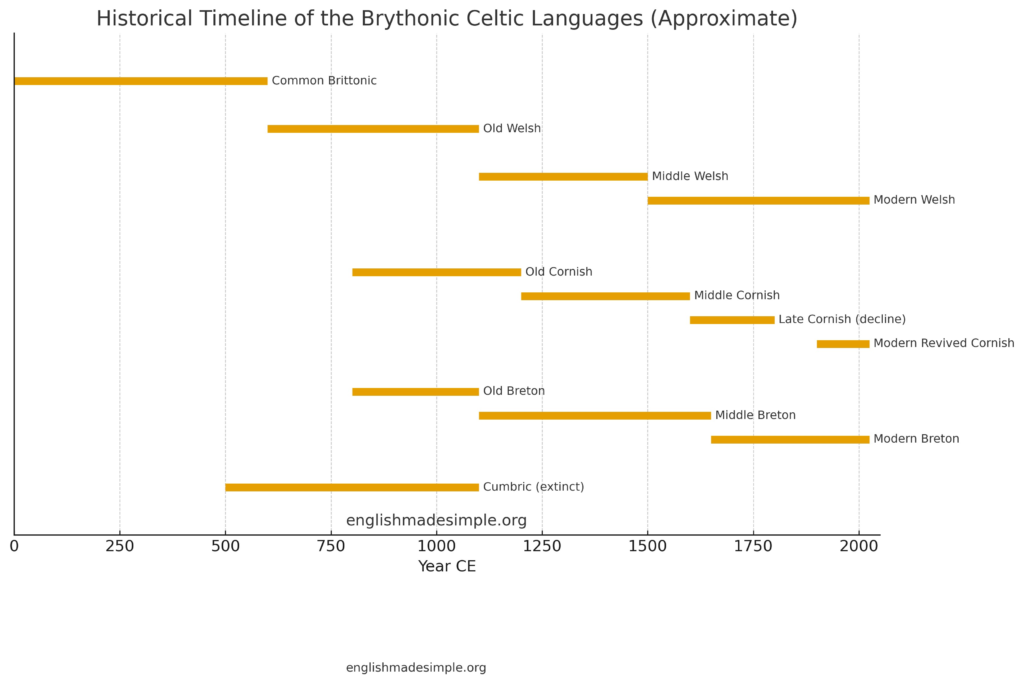

The Brythonic languages derive from a common ancestor often called Common Brittonic (sometimes Proto-Brittonic).

This language was spoken across much of what is now Great Britain during the Iron Age and Roman periods (roughly from perhaps the mid first millennium BC through into the early medieval centuries).

During the Roman occupation of Britain, Common Brittonic underwent influence from Latin (through administration, place-names, and church/literary vocabulary).

After the withdrawal of Roman rule and the influx of Anglo-Saxon (Old English) and Goidelic-Irish language influences, the Brythonic languages gradually fragmented into regional forms. Evidence suggests by the 5th–6th centuries CE large scale divergence of dialects and migration (for example to Brittany, France) of Brittonic speakers.

The name “Brythonic” comes from the Welsh word Brython (meaning Briton) and was coined by the Welsh Celticist John Rhys in the 19th century.

Development and Sub-Branches

Common Brittonic → Neo-Brittonic

The period of Common Brittonic gradually gave way by ~6th century CE into what is sometimes termed Neo-Brittonic, in which key sound changes, morphological innovations (such as loss of final syllables, syncope, and introduction of systematic consonant mutation) began to appear.

From this stem, the main Brythonic languages emerge, typically grouped as follows:

-

Welsh – The most continuous descendant of Brittonic in what is now Wales. Scholars date the transition to Old Welsh etc. by ~8th–11th centuries.

-

Cornish – The language of Cornwall (south-west Britain). Diverged from Brittonic, likely from a south-western branch, and later underwent decline, extinction (as community spoken) and revival.

-

Breton – Carried to the continent: Brittonic-speaking migrants settled in what is now Brittany (Bretagne) in north‐western France; the language evolved there as Breton.

-

Cumbric (extinct) – Once spoken in the “Old North” (northern England / southern Scotland) region until roughly the 10th–12th centuries.

-

Possibly Pictish (if considered Brythonic or a sister language) – some scholars regard the Pictish language of northern Scotland as a close relative of Brittonic, though the evidence is limited.

Within this grouping, a further subdivision is sometimes made: for instance, Southwestern Brythonic / “Southwest Brittonic” comprising Cornish + Breton ((see article on Southwestern Brittonic).

Timeline of major developments

-

Iron Age / Roman Britain (pre-5th century): Common Brittonic widely spoken.

-

5th–6th centuries: Migration to Brittany, Anglo-Saxon advance, Gaelic penetration leading to fragmentation.

-

Medieval period (c. 8th–14th centuries): Old Welsh, Middle Welsh, Old Cornish, etc. Welsh develops written literature; Cornish attested in Middle Cornish period; Breton evolves on continent.

-

Early modern to modern: Cornish decline and revival; Welsh continuous with modern revival; Breton regional status; Cumbric extinct.

Features, Differences and Similarities within Insular Celtic

Although Brythonic and Goidelic share the Insular Celtic heritage, there are both shared features and distinctive traits.

Shared Insular Celtic features include (among others):

-

verb-initial (VSO) clause structure in many historical contexts

-

initial consonant mutations (especially in Brythonic)

-

inflected prepositions (especially in Goidelic, but related prepositional phenomena in Brythonic)

-

reduction of final syllables and morphological simplification compared to Continental Celtic

Distinctive Brythonic features:

-

Brythonic languages are traditionally classified as P-Celtic, meaning that the Proto-Celtic kʷ* reflexes as p (e.g., Brittonic *p instead of Goidelic *k/c).

-

Mutation systems in Brythonic are particularly prominent (initial consonant change triggered by grammatical environment).

-

Some sound-changes and morphological developments differ compared to Goidelic.

Below is a table summarising lexical and grammatical similarities and differences between Brythonic and the Goidelic branch (within Insular Celtic).

| Feature | Brythonic languages | Goidelic languages |

|---|---|---|

| Reflex of Proto-Celtic *kʷ | Becomes p (hence “P-Celtic”) (e.g., Brittonic *pemp “five”) | Becomes k/c/q (“Q-Celtic”), e.g., Old Irish *coíc “five” |

| Initial consonant mutation | Highly developed: consonant mutation triggered by particles, possessors, prepositions (e.g., Welsh pen “head” → ben) | Less marked mutation system (though lenition/eclipsis in Goidelic) |

| Word order | Frequently VSO historically (Old Welsh) | Also verb-initial historically (Old Irish) |

| Prepositional inflection | Some inflected prepositional forms; more use of independent prepositions | More systematic inflected prepositions (Irish agam “at me”, etc) |

| Case morphology | Old Brittonic had case distinctions; modern Brythonic have reduced case systems and rely more on prepositions | Old Irish had more richly inflected case system; modern Gaelic languages have reduced case morphology |

| Lexical borrowing | Strong Latin influence (via Roman Britain) and later English/French contact in Brythonic zones | Also heavy Latin (via church/monastic Irish) and Norse/English influence in Goidelic zones |

| Survival and revival | Welsh thriving; Cornish revived; Breton regional; Cumbric extinct | Irish official status; Scottish Gaelic minority but strong institution; Manx revived from near extinction |

Comparison of the Individual Brythonic Languages

Here is a table summarising key facts about the major Brythonic languages (both living and extinct) for comparison:

| Language | Region / status | Development notes | Current status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Welsh (Cymraeg) | Wales (UK) | Evolved from Common Brittonic > Old Welsh > Middle Welsh > Modern Welsh. Continuous literary tradition from medieval period. | Living with strong revival and official status; largest Brythonic speaker base |

| Cornish (Kernowek) | Cornwall (south-west England) | Diverged from Brittonic; Middle Cornish attested; declined by 18th / 19th centuries. | Revival language; now taught, some new speakers, cultural use |

| Breton (Brezhoneg) | Brittany (north-western France) | Brought by Brittonic migrants to Brittany in early medieval period; developed separately on continent. | Regional minority language; ongoing maintenance, though under pressure from French |

| Cumbric | Northern England / southern Scotland (“Hen Oggledd”) | Once Brittonic-speaking region; Cumbric diverged from Brittonic; little direct attestation. | Extinct (approx. by 12th century) |

| (Possibly) Pictish | Northern Scotland | Some scholars consider Pictish a Brythonic variety or sister; evidence fragmentary. | Extinct |

History and Development in Detail

Iron Age and Roman Britain

During the Iron Age, the Celtic languages (including Brittonic) were spoken widely across Britain. With Roman conquest, Latin influence reached the Brittonic-speaking population. Following the Roman departure, language shift began in many areas: Germanic (Anglo-Saxon) and Goidelic (Irish) influences encroached, especially from the 5th century onward.

Early Medieval Period

In the 5th–6th centuries, large-scale migration of Brittonic peoples to what is now Brittany took place, giving rise to Breton. Meanwhile, those Brittonic speakers who remained in Wales, Cornwall, and the Old North (Cumbria, Strathclyde) gradually evolved local dialects. The language of the Old North (Cumbric) gradually disappeared under pressure from Old English and Scots Gaelic.

Medieval Literary Period

Welsh developed a strong literary tradition: Old Welsh texts survive from around the 8th–11th centuries, followed by the Middle Welsh era (12th–14th centuries) with rich poetry and prose.

Cornish, though less literarily illuminated, shows attested Middle Cornish texts in the later medieval period. Breton, though evolving on the continent, shows medieval manuscript evidence and later printed literature.

Modern Era

From the early modern period onward, Brythonic languages faced declining domains of use. Cornish lost most native speakers by the 18th/19th century; Cumbric had ceased to function centuries earlier. Welsh retained a comparatively robust speaker base, and in the 20th/21st centuries policy and revival efforts have strengthened it. Breton continues as a regional language of France, but faces pressures from French and globalization. Cornish revival from the mid-20th century onward has created a growing second-language speaking community.

Throughout, Brythonic languages have continually absorbed loans (Latin during Roman times, English/French in later centuries), and have been influenced by contact phenomena (e.g., English-Brythonic bilingualism, language shift).

Significance and Contemporary Issues

The Brythonic languages are of considerable linguistic, cultural and historical significance. They preserve distinctive Celtic structural features (mutation systems, verb-initial orders, inflected prepositions in historical forms) and provide windows into the linguistic landscape of the British Isles before and during the early phases of the English language. For example, many place-names in Britain (especially in Wales, Cornwall, Cumbria) derive from Brittonic roots.

In the modern era, questions of language revival, minority language rights, bilingual education (particularly in Wales and Brittany) and cultural identity are closely intertwined with Brythonic languages. Their ongoing vitality (Welsh), revival (Cornish), or endangered status (Breton) reflect broader patterns of minority language survival in Europe.

Conclusion

The Brythonic (Brittonic) Celtic languages constitute a major branch of the Insular Celtic family. From their origin in Common Brittonic across Iron-Age and Roman Britain, through segmentation into Welsh, Cornish, Breton (and extinct siblings such as Cumbric), to the modern era of revival and maintenance, their history is rich and complex. Their structural features both align them with their Insular Celtic cousins and distinguish them in typological and historical detail. For anyone interested in the Celtic languages, British linguistic history or minority language policy, the Brythonic branch offers a fascinating case study.