“Checking Out Me History” by John Agard – GCSE poetry

The poem:

Checking Out Me History by John Agard

Dem tell me

Dem tell me Wha dem want to tell me

Bandage up me eye with me own history

Blind me to me own identity

Dem tell me bout 1066 and all dat

Dem tell me bout Dick Whittington and he cat

But Toussaint L’Ouverture

No dem never tell me bout dat

Toussaint

A slave

With vision

Lick back

Napoleon

Battalion

And first Black

Republic born

Toussaint de thorn

To de French

Toussaint de beacon

Of de Haitian Revolution

Dem tell me bout de man who discover de balloon

And de cow who jump over de moon

Dem tell me bout de dish ran away with de spoon

But dem never tell me bout Nanny de maroon

Nanny

See-far woman

Of mountain dream

Fire-woman struggle

Hopeful stream

To freedom river

Dem tell me bout Lord Nelson and Waterloo

But dem never tell me bout Shaka de great Zulu

Dem tell me bout Columbus and 1492

But what happen to de Caribs and de Arawaks too

Dem tell me bout Florence Nightingale and she lamp

And how Robin Hood used to camp

Dem tell me bout ole King Cole was a merry ole soul

But dem never tell me bout Mary Seacole

From Jamaica

She travel far

To the Crimean War

She volunteer to go

And even when de British said no

She still brave the Russian snow

A healing star

Among the wounded

A yellow sunrise

To the dying

Dem tell me

Dem tell me wha dem want to tell me

But now I checking out me own history

I carving out me identity

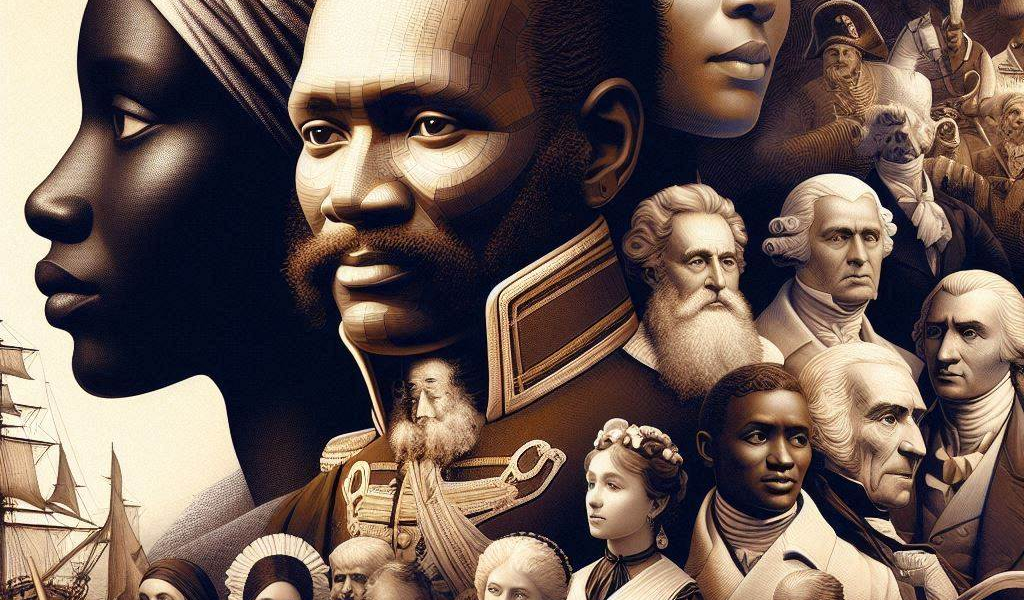

John Agard’s poem “Checking Out Me History” is a powerful and provocative exploration of identity, history, and the effects of colonial education. Through vibrant imagery, non-standard English, and a stark contrast between the dominant and the oppressed narratives, Agard challenges the Eurocentric version of history taught in schools and asserts the importance of understanding one’s cultural heritage.

Historical Context

John Agard was born in British Guiana (now Guyana) in 1949, a country that was once a British colony. Like many Caribbean writers, Agard addresses the consequences of colonialism, particularly how it affects national and personal identity. The British colonial education system often marginalised or completely omitted the achievements and experiences of non-European peoples. For Agard, this meant growing up learning about white British figures like Lord Nelson or Florence Nightingale, while not hearing about influential Black or Caribbean figures.

“Checking Out Me History” was first published in 2007 and became part of the AQA Power and Conflict anthology, where it stands out as a contemporary poem that focuses on identity and resistance rather than war or physical conflict. However, the “conflict” in this poem is ideological and cultural—one of knowledge, representation, and power.

Themes

1. Power and Identity

Agard emphasises the power of history in shaping identity. He argues that by controlling historical narratives, institutions also control how people see themselves and their place in the world. The poem critiques how colonial history erases Black identity and heritage.

“Dem tell me / Dem tell me / Wha dem want to tell me”

This refrain highlights the selective telling of history. “Dem” refers to the British education system and wider institutional powers.

2. Resistance and Empowerment

The act of “checking out” history is one of resistance. By reclaiming and celebrating Black historical figures, Agard empowers both himself and others who share his background.

“But now I checking out me own history / I carving out me identity”

This final line is crucial—it shows the transformation from passive recipient of biased knowledge to an active seeker and creator of truth.

3. Colonialism and Historical Erasure

The poem interrogates the legacy of colonialism, particularly how it distorts or omits history. The figures of Black resistance and resilience (e.g., Toussaint L’Ouverture, Mary Seacole) are placed alongside critiques of the Eurocentric canon taught in British schools.

Key Quotes and Analysis

“Dem tell me / Dem tell me / Wha dem want to tell me”

-

Repetition and colloquial phrasing establish a defiant tone.

-

The word “Dem” suggests a division—us vs. them, highlighting the speaker’s alienation from the educational system.

-

This phrase reinforces the idea of narrative control and propaganda.

“Bandage up me eye with me own history / Blind me to me own identity”

-

Metaphor of being “bandaged” and “blinded” suggests deliberate concealment.

-

It implies that the speaker’s understanding of self has been damaged by a lack of representation.

-

Strong imagery shows how historical distortion can hurt one’s perception of self.

“Toussaint L’Ouverture / No dem never tell me bout dat”

-

Short, emphatic line; the single-name focus draws attention to the poet’s frustration.

-

Toussaint was a key leader of the Haitian Revolution—he represents Black resistance.

-

The fact that he is omitted from the mainstream syllabus is symbolic of wider systemic bias.

“A healing star / among the wounded / a yellow sunrise / to the dying”

-

This description of Mary Seacole uses natural imagery and metaphor to elevate her.

-

She becomes a symbol of hope and strength, countering the erasure of Black contributions.

Literary Devices

Agard uses a range of techniques to convey his message and deepen the poem’s impact:

1. Non-Standard Phonetic Spelling

“Dem” instead of “them”; “me” instead of “my”

-

This reflects Agard’s Caribbean heritage and dialect.

-

It challenges “correct” English and asserts the validity of his cultural voice.

-

It also makes the poem feel oral and rhythmic, echoing traditions of storytelling and performance poetry.

2. Contrast and Juxtaposition

-

Agard juxtaposes European figures like Florence Nightingale and Dick Whittington with figures like Nanny de Maroon and Shaka the Zulu.

-

The European figures are often presented as generic or unimpressive, while the Black historical figures are vivid and heroic.

E.g., “Florence Nightingale and she lamp / and how Robin Hood used to camp” vs. “Toussaint de beacon / of de Haitian Revolution”

3. Imagery and Symbolism

-

Rich metaphors and symbols are used to describe the figures Agard celebrates.

-

Mary Seacole is likened to sunlight and healing, elevating her status.

“A healing star / among the wounded”

4. Structure and Form

-

The poem switches between italicised stanzas (about Black historical figures) and the regular stanzas (repeating “Dem tell me”).

-

The italics highlight the contrast in tone and purpose: celebration vs. critique.

-

Free verse and lack of punctuation reflect rebellion against rigid structures, much like the speaker rebels against the education system.

Challenging Language Explained

Some words or phrases may confuse a modern UK teenager:

-

“Dem” – Caribbean dialect for “them.”

-

“Bandage up me eye” – Metaphor for being blinded or prevented from seeing the truth.

-

“Nanny de Maroon” – A Jamaican national hero who led resistance against British colonisers.

-

“Shaka de great Zulu” – A powerful Zulu king known for military innovation in Southern Africa.

-

“Carving out me identity” – Suggests creating or reclaiming one’s self-image, often against resistance.

Comparison with Other AQA Power and Conflict Poems

Agard’s poem can be powerfully compared with several others in the anthology, especially those dealing with identity, power, or resistance.

1. “The Emigrée” by Carol Rumens

-

Both poems explore identity and displacement.

-

The speaker in The Emigrée reminisces about a homeland suppressed by an unnamed authoritarian force, similar to how Agard longs for recognition of a history obscured by colonialism.

-

Both use personification and imagery to express longing for truth and connection.

2. “Kamikaze” by Beatrice Garland

-

This poem also examines personal and national identity, and how state-imposed narratives can conflict with personal values.

-

Both poets consider what happens when individuals reject the official narrative.

3. “London” by William Blake

-

A strong comparison due to criticism of institutions—Blake criticises Church and monarchy, while Agard critiques education and colonial ideology.

-

Both use repetition and imagery to highlight suffering and oppression.

4. “Ozymandias” by Percy Shelley

-

Offers an ironic take on power and legacy.

-

Like Agard’s message, Shelley implies that those in power will be forgotten, while those truly impactful (like Seacole or Toussaint) deserve remembrance.

-

Both critique arrogance and the fleeting nature of domination.

How to Get a Grade 9

Achieving a Grade 9 in GCSE English Literature requires more than just identifying techniques—it involves offering original, conceptual insights and writing with clarity and depth. Here’s how to approach Checking Out Me History in a way that can secure a top grade:

1. Understand Context Deeply

-

Go beyond just “colonialism.” Explore how curriculums are shaped by ideology and how language can reinforce systemic bias.

-

Show awareness of Agard’s personal context as a Caribbean-British poet writing in a post-colonial Britain.

2. Use Comparative Analysis

-

Don’t just analyse this poem in isolation. Always relate it to at least one other poem from the anthology—doing this fluently is a hallmark of a top-grade answer.

-

Make nuanced comparisons—not just “both use imagery,” but how and why they use it differently.

3. High-Level Terminology

Use terms like:

-

“subversion of form”

-

“narrative authority”

-

“postcolonial discourse”

-

“juxtaposition of oral tradition and institutional rhetoric”

4. Sophisticated Structure

-

Begin with a strong thesis (e.g., “Agard reclaims marginalised narratives to challenge imperial dominance and assert cultural identity.”)

-

Organise points thematically (e.g., “Education and Control”, “Rebellion Through Language”, “Historical Memory”).

5. Close Analysis

-

Zoom in on key words (e.g., “carving” suggests effort, creativity, and struggle).

-

Analyse not just what’s said, but what’s implied. For example, by italicising non-European figures, Agard ironically gives them more emphasis than traditional figures.

Conclusion

“Checking Out Me History” is a radical and lyrical demand for recognition—a poem that rewrites history in the poet’s own terms. By challenging the dominant historical narrative, Agard asserts the need for cultural inclusivity and self-defined identity. Through the use of non-standard dialect, rich imagery, and juxtaposition, the poem becomes both a critique and a celebration—one that resonates strongly in contemporary conversations about decolonising education and history.

For students studying this poem, achieving a Grade 9 means digging into the layers of voice, power, and resistance that Agard offers—and writing with flair, precision, and critical insight.