The Welsh Language Family

Classification and Family Relations

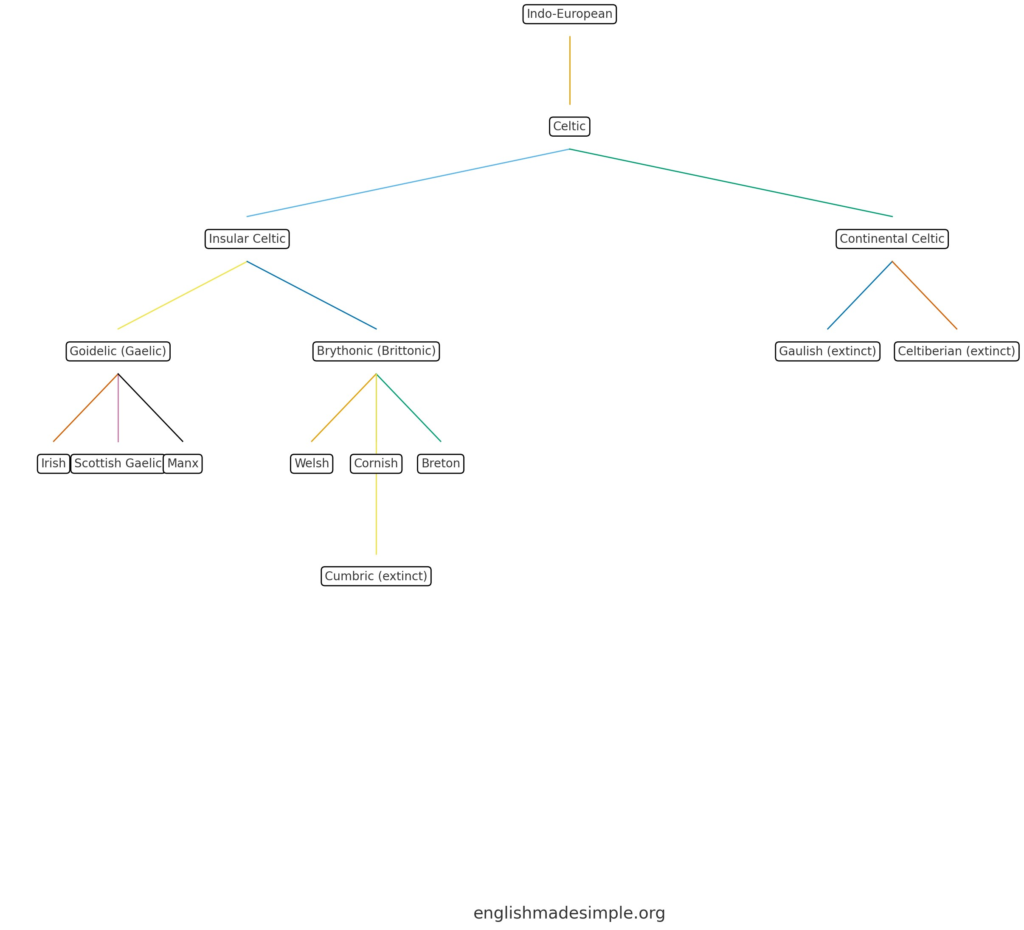

The language commonly known as Welsh is properly the language of the nation of Wales — the standard variety is commonly referred to as Welsh (in Welsh: Cymraeg). It belongs to the Brythonic branch of the Celtic family of Indo-European languages. Let us set out the hierarchy:

-

The largest relevant grouping is the Indo-European family: a very large language-family including English, Germanic languages, Romance languages (French, Spanish, Italian), Baltic, Slavic, Indo-Iranian, and the Celtic languages among others.

-

Within that family is the Celtic sub-group.

-

Within the Celtic group there are two primary branches: Goidelic (or Gaelic) and Brythonic (also spelt Brittonic). The Brythonic branch includes Welsh (Cymraeg), Cornish (Kernewek) and Breton (Brezhoneg), among others.

-

Thus Welsh is one of the Brythonic languages; that branch is distinct from the Goidelic branch (Irish, Scots Gaelic, Manx).

-

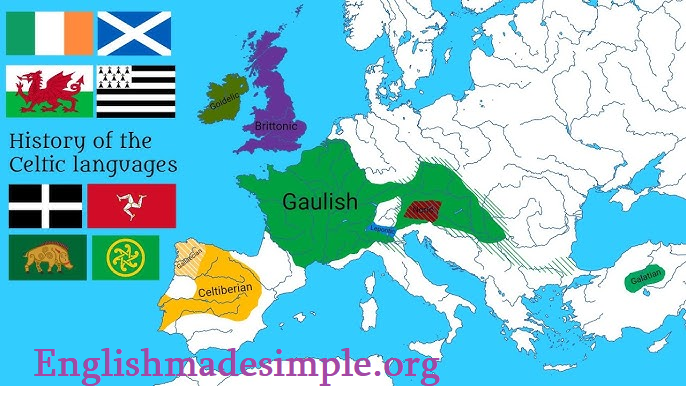

In addition, the Goidelic and Brythonic together form the Insular Celtic languages (i.e., Celtic languages of the British Isles) as opposed to the Continental Celtic languages (now extinct) such as Gaulish, Celtiberian.

So, to summarise: Welsh → Brythonic → Celtic → Indo-European.

Within the Brythonic branch there is no large further division of “sub-families” in the sense of many distinct languages with long independent development; rather, Welsh is one of the three surviving Brythonic languages (Welsh, Cornish, Breton). Historically there were more Brythonic languages/dialects across ancient Britain (for instance, Cumbric in the north of England / southern Scotland, Pictish possibly related) but these became extinct or merged.

Origins, History and Development

Early Origins

The story begins with the arrival of Celtic-speaking peoples in Britain. It is generally held that the Celtic languages began to spread into Britain from around the middle of the 1st millennium BC, though exactly how is debated. Over the centuries the Celtic languages of Britain diversified into multiple local dialects of the Brythonic branch.

By the time of the Roman occupation of Britain (from 43 AD onwards in southern/traditional Britain), Celtic languages were already well established. After the Roman withdrawal (early 5th century) the Brythonic languages continued evolving. We see evidence of a so-called Common Brythonic stage (sometimes called “British” or Brittonic) out of which modern Welsh, Cornish and Breton later emerged.

Old Welsh (approx. 6th to 11th centuries)

In the post-Roman period (6th-8th centuries) what we may call “Old Welsh” began to emerge. The earliest surviving inscriptions in Welsh date from around the 8th / 9th centuries (e.g., the “Cadfan stone”). In this period the language was developing from Common Brythonic, undergoing changes in phonology, morphology and syntax. Wales (the region) was divided into various kingdoms (Gwynedd, Powys, Dyfed, etc.), each with its dialectal features, but the overall language was recognisably Brythonic.

In this era, the language had strong links with the literate culture of the Celtic Church, and the earliest medieval Welsh poetry and prose begin to appear. For example, the 9th- to 11th-century Welsh law texts (Laws of Hywel Dda) show a mature Old Welsh system.

Middle Welsh (c. 12th to 14th centuries)

From around the 12th century, “Middle Welsh” became the dominant written form of Welsh. This is the language of the classic medieval Welsh prose (such as the Mabinogion) and poetry. It shows many grammatical features similar to modern Welsh, but also visible differences: for example, more case inflection on nouns, more flexion on adjectives, and more variety of verb forms. The literature of this period is rich: e.g., the saga-style narratives, bardic poetry, historical chronicles.

Modern Welsh (15th century to present)

By the 15th century onwards, the language evolves toward what linguists call Modern Welsh. Standardisation begins to appear especially from the 16th century, when the Bible was translated into Welsh (William Morgan’s Welsh Bible, 1588). From then, printing, the rise of formal education, and later the 19th- and 20th-century revival efforts all contributed to the form of Welsh spoken and written today. Dialect variation remains strong (North Welsh vs South Welsh, and local Welsh dialects), but the standard language (based on the work of e.g., the University of Wales and the Welsh Government) is widely used.

Welsh in relation to English: historical and modern

Historically, Welsh and English have had a complex relationship. With the Norman / English conquest of Wales and subsequent incorporation of Wales into the English/UK state, English became the dominant language for government, law, commerce and education from roughly the 16th century onwards. Welsh was marginalised; the 1536 and 1542 Acts of Union required English to be the language of law and administration in Wales.

In the 19th century, industrialisation, migration (into South-Wales coalfields) and English-medium schooling further reduced Welsh usage. By the early 20th century Welsh was in significant decline. However, from the mid-20th century onward there has been a revival: Welsh-medium education, official bilingual policy, Welsh language broadcasters (e.g., S4C), and legislative protection (Welsh Language Act 1993, Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011) all revived the status of Welsh.

In modern Wales (the country of Wales) Welsh and English commonly coexist. Welsh is an official language, equal status with English in certain public contexts. Many citizens are bilingual, and Welsh is taught in schools across the country. The relationship is also dynamic: Welsh sometimes enjoys higher prestige (schooling, media, government) than in the past; however English remains dominant in commerce, popular culture and international domains. In bilingual settings, code-switching, loan-words and interplay between Welsh and English are common.

Emergence of Sub-Branches and Dialects

While the Brythonic branch essentially gave rise to three surviving languages (Welsh, Cornish, Breton), within Welsh-speaking territory different dialects and varieties have developed over time:

-

North Welsh dialects (e.g., Gwynedd) vs South Welsh dialects (e.g., Glamorgan). Differences appear in vowel pronunciation, intonation, certain vocabulary and syntax.

-

Mid Wales dialects such as Ceredigion often show transitional features.

-

Welsh English varieties (Welsh via English influence) also develop: for example “Welsh English” features certain Welsh-influenced syntax or vocabulary (often called Cymraeged English).

-

Though not formal “sub-branches” in the sense of major splits, the history of Welsh also includes the older forms (Old Welsh, Middle Welsh) which may be thought of as successive “stages” rather than completely separate branches.

In the broader Brythonic branch:

-

Cornish (once widely spoken in Cornwall) developed independently, separated from Welsh by geographic and political factors; its revival in the late 20th/21st century means it now exists as a revived language.

-

Breton in Brittany (north-western France) arose when Brittonic-speaking migrants from southwest Britain settled in Armorica in the early medieval period. Breton thus shares common origin with Welsh but adopted its own trajectory influenced by French and Breton local languages.

Thus the “sub-branches” within the Brythonic family are roughly these languages plus extinct dialects such as Cumbric (in northern Britain) and Pictish (possibly related). Welsh, Cornish and Breton are the main ones lately.

Grammar of Welsh (Intermediate Level)

Here we discuss key grammatical features of Welsh: vocabulary structure, articles, demonstratives, word order, verbs (conjugation, tenses) with example sentences.

Definitite and Indefinite Articles

Welsh has both definite and indefinite articles:

-

Indefinite article: un (one/a) — used like English “a, an”.

-

Example: un cath “a cat”.

-

-

Definite article: y / yr / ’r — equivalent to English “the”. Choice of form depends on initial vowel or consonant.

-

y ci “the dog” (y + consonant), yr u “the eagle” (yr + vowel), ’r bws “the bus” (after a following consonant cluster) etc.

-

Example sentence: Mi welais y ci ar y stryd. “I saw the dog on the street.”

-

Demonstrative Pronouns

Welsh uses demonstratives to mean “this”, “that”, etc. Typically: hwn/hon/hyn for “this (masc/fem/neu.)”, hwnnw/honno/hynny for “that”, etc. Usage is somewhat more complex because of gender and number.

-

Example: Mae hyn llyfr ar y bwrdd. “This book is on the table.”

-

Example: Dros hynny lôn mae’r tŷ. “Over that lane is the house.”

Word Order

The typical word order in Welsh is Verb-Subject-Object (VSO) in simple affirmative sentences — this is unlike Standard English (SVO). For example:

-

Ysgrifenna John lythyr. “John writes a letter.” (literally: Writes John a letter.)

-

More naturally: Mae Siân yn darllen y llyfr. “Sian is reading the book.” (Auxiliary verb + subject + …)

However, Welsh allows variation (especially with topicalisation, fronting, negative constructions, mutations) and there are SVO constructions especially in spoken Welsh and modern usage.

Verbs, Conjugation and Verb Tenses

Present tense / simple present

Welsh uses a present tense that often corresponds to English present or present-continuous. It uses the verb bod (“to be”) for auxiliary, and other verbs remain un-inflected for person (except in past). Example:

-

Dw i’n siopa. “I am shopping.” (Literally: Am I in shopping.)

-

Ysgrifenna Sian lythyr bob dydd. “Sian writes a letter every day.”

Past tense

Welsh marks the past tense with a variety of inflections depending on verb class (regular / irregular). Example of a “regular” verb: cân (“sing”). Past tense: canodd (he/she/it sang). Example sentence:

-

Canodd y grŵp o’r ysgol ganu’r gan. “The school group sang the song.”

Irregular verbs: bod (to be) has forms oedd (he/she/it was). Example:

-

Oedd Siân yn hapus. “Sian was happy.”

Future tense

Welsh uses the verb bydd (from bod) plus a noun phrase or a verbal noun to express future. Example:

-

Byddwch chi’n dod yfory. “You will come tomorrow.”

Alternatively, some verbs form the future by prefix –af for first person (especially literary). Example: -

Ysgrifennaf lythyr. “I shall write a letter.”

Modal / Verbal noun constructions

Welsh uses verbal nouns (infinitive‐like forms) often with auxiliary verbs such as gall (“can”), wyr (“know how”), dylet (“should”), hoffi (“to like”) etc. Example:

-

Dw i’n hoffi bwyta bwyd Cymreig. “I like eating Welsh food.”

Here bwyta is the verbal noun “eating”.

Examples summary

| Tense / Construction | Welsh example | English gloss |

|---|---|---|

| Present | Dw i’n gweithio. | “I am working.” |

| Simple present | Ysgrifenna John lythyr. | “John writes a letter.” |

| Past | Canodd hi y gan. | “She sang the song.” |

| Past (to be) | Oedd y ci gyda ni. | “The dog was with us.” |

| Future | Bydd hi’n ymweld yfory. | “She will visit tomorrow.” |

| Modal + verbal noun | Dw i’n gallu darllen Cymraeg. | “I can read Welsh.” |

Mutation, Prepositions and Inflected Prepositions (brief mention)

While this moves slightly beyond “intermediate”, it is helpful: Welsh features initial consonant mutation (where the initial consonant of a word changes depending on grammatical context — e.g., after certain particles, possessives, prepositions). Example: gwlad (country) → ei wlad (his country) after ei “his”. Prepositions in Welsh may become inflected with pronouns: gyda “with” → gyda fi “with me”, gyda ni “with us”.

Summary of Grammar Points

-

Indefinite article un, definite articles y / yr / ’r.

-

Demonstratives (hwn/hon/hyn etc).

-

Word order is typically V–S–O, but variation exists.

-

Verbs: present, past, future, modal + verbal noun; use of auxiliary bod.

-

Example sentences given.

-

Mutations and inflected prepositions present (briefly introduced).

Similarities and Differences with the Other Brythonic Languages

This section compares Welsh with Cornish and Breton in lexical (vocabulary) and grammatical terms. We present a table, followed by commentary.

Table – Lexical & Grammatical Comparison

| Feature | Welsh (Cymraeg) | Cornish (Kernewek) | Breton (Brezhoneg) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic vocabulary (e.g., “water”) | dŵr | dowr / dowr | dour | All share the same root from Brythonic dūro-. |

| Word order typical | VSO (in standard use) | VSO typical | VSO typical | All three show VSO heritage. |

| Definite article | y/yr/’r | an | ar / al | Cornish uses a single article; Breton two forms depending on initial. |

| Indefinite article | un | un | ur / un | All show un– type form. |

| Mutation of initial consonants | Yes (soft, aspirate, nasal) | Yes | Yes | Mutation is common to Brythonic languages. |

| Present tense verb inflection | Mostly un-inflected (apart from bod) | Similar | Similar | Divergence in auxiliary usage. |

| Vocabulary divergence (example “house”) | ty | ty / ti | ti | All share the t-y root; slight variation in spelling/pronunciation. |

| Modern revival / status | Widely used in Wales; standardised | Revived, smaller community | Widely used in Brittany (France) but under pressure | Differences in sociolinguistic status. |

Commentary on Similarities and Differences

Because Cornish, Welsh and Breton descend from a common Brythonic ancestor, they share a considerable amount of vocabulary, grammatical features (especially initial mutation, verb-noun structures, VSO word order). For example, the word for “woman” is gwraig in Welsh, gwraig in Cornish, gwreg in Breton — very similar forms.

However, differences have emerged for various reasons:

-

Geographic separation: Breton developed on the continent (Brittany) and was influenced by French; Cornish was isolated in Cornwall and underwent language decline and revival; Welsh remained in Wales with its own dialectal developments and heavy contact with English.

-

Contact with other languages: Welsh has long been in contact with English; Breton with French; Cornish with English and local dialects. These influences shape vocabulary, syntax and sociolinguistic status.

-

Standardisation and revival: Welsh has a relatively strong modern standard form, state support, media presence; Cornish is a revived language with fewer speakers; Breton is robust regionally but under pressure from French centralising policies.

-

Internal developments: Each language has developed its own phonological shifts, morphological changes and lexical innovations. For example, Welsh spells “school” as ysgol, Breton as skol, Cornish as scol. The root is the same, but spelling/pronunciation differ.

-

Grammar divergence: While mutation is common across all three, the exact rules differ; verb-inflection patterns differ; certain particles and pronouns vary. For example the definite article in Welsh shows variation y/yr/’r, while Cornish uses an regardless, Breton uses ar / al depending on initial consonant.

The Modern Status and Relationship with English in Wales

In modern Wales, Welsh and English coexist in a bilingual society. According to the latest statistics (for example from the 2021 census), a substantial proportion of Wales’s population can speak Welsh; Welsh-medium schools increase the number of young Welsh speakers; signage is bilingual; public bodies offer services in Welsh; media such as the Welsh television channel S4C broadcast in Welsh; the language enjoys legal protection and recognition (for instance the Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011 gave Welsh official status in Wales). English remains dominant in many domains (business, internet, international communication) but Welsh has seen a revival of prestige and use.

Historically, as mentioned, Welsh was marginalised during centuries of English dominance (especially during the 19th and early 20th century). But the modern policy of bilingualism and the growth of Welsh-medium education have reversed or mitigated that decline in many regions. Welsh is now taught in almost all schools in Wales (though levels of fluency vary), and many local authorities and companies operate bilingually. Code-switching between Welsh and English is common in everyday speech, and many Welsh speakers are bilingual, shifting seamlessly between the two languages.

The relationship between Welsh and English also shows interesting structural interplay: Welsh has borrowed many English loan-words (especially in technical, scientific, business vocabulary). At the same time, English spoken by Welsh speakers often shows influences of Welsh syntax or idiom (so-called “Welsh English”). For example, Welsh speaker might say in English: “I am at the house” where “at” reflects Welsh yn “in/at”, or use distinctive intonation patterns.

The Importance of Welsh Dialects and Variation

While the standard Welsh taught in schools and used in media is often based on a consensus norm drawing upon various dialects, local Welsh dialects remain vibrant, especially in more rural and Welsh-speaking areas (e.g., Gwynedd in North Wales, Ceredigion in mid-Wales, Pembrokeshire in the west). These dialects differ in pronunciation (for example, vowel quality, diphthongs), vocabulary (local words for everyday objects), idiom and sometimes even grammar (for example, variant forms of past tense verbs). The existence of dialectal variation means that while learners may study standard Welsh, they may encounter different “flavours” of the language in everyday use and community contexts.

Conclusion

In summary, the Welsh language (Cymraeg) stands as one of the surviving Brythonic Celtic languages, sharing a common ancestor with Cornish and Breton. From its origins in the Celtic-speaking Britain of the 1st millennium BC, through Old Welsh, Middle Welsh, and into the modern standardised language of Wales, it has undergone considerable change and development. Its grammar exhibits distinctive features (such as verb-subject-object order, initial consonant mutation, verbal nouns, and a two-article system). Historically, Welsh has co-existed and competed with English, and in modern Wales the relationship is collaborative and bilingual, though English remains dominant in many spheres. Comparisons with Cornish and Breton show both strong common heritage and independent innovation. This makes Welsh a fascinating language for study both linguistically and socioculturally.